IT HAS taken over a decade of painstaking work, but 1300 bones ascribed to early medieval bishops and royals — returned to six mortuary chests at Winchester Cathedral following its ransacking during the Civil War — have been matched to individuals and are to be reinterred.

The remains, many of which are believed to have been originally buried in the Cathedral’s forerunner — the Anglo-Saxon Old Minster — date from the late Anglo-Saxon and early Norman period. Names in Latin on the sides of the painted chests are Cynegils, Cynewulf, Aethelwulf, Eadred, Edmund, Cnut, William Rufus, Bishop Wine, Bishop Alwine, and Queen Emma.

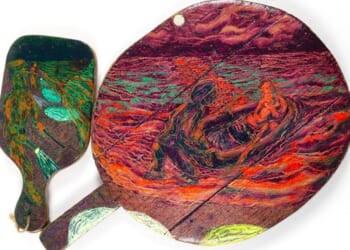

WINCHESTER CATHEDRALWINCHESTER CATHEDRAL

WINCHESTER CATHEDRALWINCHESTER CATHEDRAL

A contemporary chronicler at the time of the Minster demolition noted that “kings were mixed with bishops and bishops with kings”. An 1685 account of Oliver Cromwell’s ransacking of the Cathedral in 1642 describes how soldiers “threw down the Chests, wherein were deposited the bones of the Bishops, the like they did to the bones of William Rufus, of Queen Emma, of Hardecanutus and [. . .] all the rest of the West Saxon Kings.”

Several chests were destroyed. Four survived, and two were later recreated. Their contents were reported to have been scattered across the pavement of the Cathedral. Having smashed all the windows that they could reach, soldiers were then reported to have thrown bones at those out of reach, “with their swords, muskets or rests”.

The Mortuary Chests Project began in 2012 and has involved specialist academics, conservators, cathedral staff, and volunteers, including a team of biological anthropologists from the University of Bristol.

By 2019, at least 23 partial skeletons had been reconstructed, and there was a suggestion that one of these was Queen Emma, daughter of Richard I, Duke of Normandy, the wife of two successive Kings of England, Ethelred and Cnut, and mother of King Edward the Confessor and King Hardacnut.

Professor Kate Robson Brown, who led the investigation, told the Church Times at that time: “We cannot be certain of the identity of each individual yet, but we are certain that this is a very special assemblage of bones.” (News, 17 May 2019)

Winchester Cathedral’s curator, Eleanor Swire, said that the project demonstrated “the combined power of science, the study of human remains and historical research to discover new information about the six mortuary chests and their occupants which would not have been available to us a generation ago”.

Radiocarbon dating has guided the reinterment, with individuals from broadly similar periods placed together in the same chest. The project’s findings on the individuals in the chests are expected later this year, and will be “highly significant in the fields of archaeology, history and genetics”, a statement from the cathedral suggests.