THE General Synod voted almost unanimously on the Tuesday for a motion referring to the Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life ) Bill and calling on the Government to support palliative care rather than enact “a law that puts the most vulnerable at risk”.

Moving the motion, the Bishop of London, the Rt Revd Sarah Mullally, said that a peaceful death, for self and loved ones, was the desire of people on both sides of the debate. But she was profoundly concerned by the move to legalise assisted suicide. This was based on theology, policy, and her own experience as a nurse, caring for the dying. The Church’s opposition had always been grounded on its calling to protect the vulnerable, she said.

On top of a principled objection to assisted suicide, there were specific issues with the Bill currently with Parliament. In a context in which only 30 per cent of hospice care was funded by the NHS, it was “unthinkable” that the state should choose to fund assisted dying fully, she said. The Government’s own equality assessment recognised that the many protected groups, including disabled people, women, and people vulnerable to coercion, might be disproportionately affected.

The Church must take life after death seriously and, therefore, resist “death-dealing practices” exemplified by this Bill. Every person held “immeasurable value”, which could not be diminished by physical ailments or loss of faculties. “A Church whose hands are consecrated to bring life cannot support the prescription of life-ending drugs,” she concluded.

Dr Nick Land (York) recalled meeting a Belgian undertaker and part-time death doula who supported families as they approached an assisted suicide. The doula had observed that “assisted suicide was a disaster” for many of the families, especially when children were divided over the decision of a parent to seek to end their life: she regularly saw families who were “angry that their parents had deserted them” or ashamed, feeling that they were “not enough” to keep them alive. Dr Land said that the protections in the Bill were inadequate, but no protection could stop families from tearing themselves apart once assisted suicide became available. “This is a line our nation must not cross.”

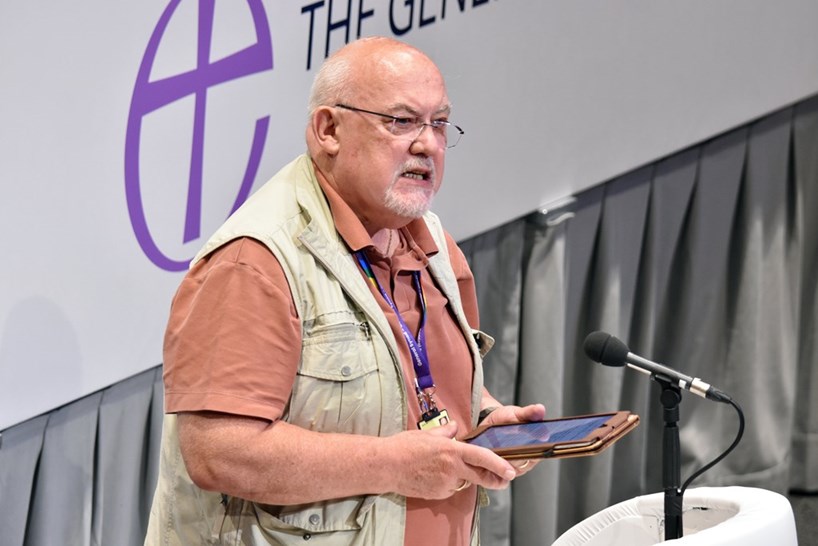

Sam Atkins/Church TimesDr Nick Land (York)

Sam Atkins/Church TimesDr Nick Land (York)

Philip Baldwin (London) was in favour of assisted dying, and thought that the current Bill was close to the required protections. Helping people to die well was “loving, kind, and compassionate”, he said, and in line with Christian practice. Those who sought to die should not be “shamed by the national Church”. His initial opposition had been changed since listening to those who had suffered at the end of life. The Bill was about providing choice, he argued; even if only a few took it up, many more would be comforted by knowing that the option was there. “We must not allow assisted dying to become stigmatised, and force people to choose between a peaceful death and their faith.”

The Revd Dr Charlie Baczyk-Bell (Southwark) thanked Bishop Mullally for her careful speech, and echoed Dr Land’s hostility to the Bill’s psychiatric assessments. He also opposed assisted dying on principle, owing to its risks to the most vulnerable. This proposed change to the law shifted something important in society’s approach to death, he suggested, which would undermine the hospice movement (itself founded by a Christian, Dame Cicely Saunders), and would affect the doctor-patient relationship. He cautioned against members’ hectoring others who disagreed with them and urged the Church to utilise the expertise of the laity.

The Revd Jonathan Macy (Southwark) had previously worked in care homes with people with learning difficulties. He recalled one resident, Albert, who had Down’s Syndrome, and who at one time became seriously unwell and ended up in intensive care. It was not long before one of the doctors was wondering how they could withdraw care and “let things take their course”. That conversation was being had only because Albert was disabled, Mr Macy said. “You can’t treat people like that, especially ones without a voice.” He and colleagues stayed at Albert’s side until he recovered, and he lived for several happy years. The Church must continue defending care for those who did not have a voice, Mr Macy said.

Dr Simon Eyre (Chichester) quoted a verse from Isaiah about God’s sustaining people into old age. Jesus regarded everyone with great care, Dr Eyre said, and so must his followers. But hospices were in crisis owing to a lack of funds; nobody would expect other parts of the NHS to be dependent on charitable giving, but only 25 per cent of hospice funding came from the State. Medical organisations had come out in opposition to assisted suicide.

Prudence Dailey (Oxford) said that she was a full-time carer for her 92-year-old mother, who had recently told her that she had lived too long. But Miss Dailey said that she intended to make every remaining day as happy as it could be. In one sense, her mother was a burden on Miss Dailey’s life, but so had she been to her mother as a premature baby. “We are burdens to one another.” The most common reason that people chose assisted suicide was a fear of being a burden, she said. “Send a clear message where the Church stands on this issue.”

Sam Atkins/Church TimesPrudence Dailey (Oxford)

Sam Atkins/Church TimesPrudence Dailey (Oxford)

The Bill would change society for ever, Piyush Jani (Ely) warned. “How we care for the weak and the dying defines our society.” As a consultant surgeon and a son whose mother had recently died of cancer, he had sat at the bedside of many approaching death. Choice was rarely exercised in a vacuum, he warned, and those facing terminal illness had their thinking profoundly affected by loneliness and “internal coercion” by their fears of being a burden. There was also a risk that limited NHS resources would be diverted from underfunded palliative care to a state suicide service.

Bradley Smith (Chichester) praised Bishop Mullally for standing up for the God-given dignity of human life and for those who served in hospices caring for the dying, including chaplains. “The future of Christian hospitals and institutions will be under threat” if the Bill was passed. He hoped that there was still time for the Church to “turn back public opinion” on assisted suicide.

The Revd Robert Thompson (London) asked how the Church came to its position on assisted suicide. There had been a 2022 motion carried overwhelmingly in the Synod, but, he suggested, this had “bundled in” palliative care with assisted suicide. He was not, in principle, against assisted dying, informed by his eight years as a hospice chaplain, but the safeguards in the Bill could still be improved. He would, he said, be voting against the motion. because it asked the Government not to enact the Bill. This was “democratically unacceptable”. “We choose whether we have anaesthetic or other medical interventions, and I hope we can choose to enable those to end their lives,” he concluded.

The Revd Martin Davy (Oxford) said that the daughter of a members of his congregation had been given months to live after being diagnosed with cancer, but was now entirely cancer-free years later. He wondered what would have happened had assisted suicide had been an option. He did not want to diminish the suffering that the dying went through, but the gospel called on Christians to “take heart” and stand with the suffering of Christ. Disease, disability, or dementia could not rob humans of their God-given dignity, he said. “Dependency is not a threat to our dignity, but an invitation to love.” A compassionate society should not believe in relieving others of the burden for caring for them.

Fiona MacMillan (London) said that assisted-suicide legislation had been extended to disabled people in Canada only a few years after the law came into force. Canada set a “terrifying precedent” of the slippery slope, should assisted dying become legal here. The UK, she said, was an increasingly unsafe place to be disabled, with its cuts to benefits and rising hate crime. She urged members to back the motion and demand that the Government protect vulnerable people.

Dr Alan Dowen (Chester) said that he would hate to finish his life “racked in uncontrollable pain” and that, while he could not support the motion, he affirmed his own belief that every person regardless of age or infirmity was of immeasurable value. Giving people permission to end their own suffering was an act of love, he suggested; “so can it really be contrary to God’s law?” Even with good palliative care, some people would die with pain and indignity, he suggested.

Abigail Ogier (Manchester) was ambivalent over assisted dying, she said, because her life was not hers to determine, but belonged to God. She was in favour of “excellent” palliative care, especially after her experience serving in a hospice during the pandemic.

Sam Atkins/Church TimesDr Alan Dowen (Chester)

Sam Atkins/Church TimesDr Alan Dowen (Chester)

Dr Laura Oliver (Blackburn), a GP, said that one of her cancer patients had consistently sought to end his life after his diagnosis. He would have met the criteria of the Bill comfortably, but her team had given him support, including offering him a psychologist, who helped him. The best answer to fear of suffering was not death, but support to live, she said. Instead of choosing to die, her patient had been given the opportunity to live well for the time that God had given him, and recently celebrated his grandson’s birthday. “Every person is precious to God and made in his image,” she concluded.

Jane Patterson (Sheffield), an NHS surgeon and medical examiner, said that the shift to palliative care at the end of a person’s life often took too long. “Many live in denial that natural death is the end of life on earth,” she said, which was ultimately a spiritual problem that the Church must speak into. Most people did not die in agony or distress, but the quality of life in the final days could be improved by an earlier focus on palliative care, she suggested, and urged members to pray for the House of Lords as it discussed the Bill.

The Bishop of Blackburn, the Rt Revd Philip North, said that his father — who had died a few months ago — would have been a prime candidate for assisted suicide. During his final days, holding his hand, Bishop North had realised how wrong it would have been to end his life artificially. He already knew the strong arguments against assisted suicide, but had felt something “raw and visceral” that it would be utterly wrong to take away life, which was a gift of God. “Undermining life in any context takes away something of its beauty and its mystery.”

Fr Thomas Seville CR (Religious Communities) said that everyone was wonderfully made to live and die. All the Abrahamic faiths shared a caution against assisted suicide, he said.

The Revd Paul Cartwright (Leeds) said that society was being asked to accept the idea that some lives were “not worth living”. It might sound compassionate at first glance, but he had been placed in palliative care in 2009. If he had ended his life then, he would have missed seeing his children grow up. He warned of a slippery slope after legalisation, stretching assisted dying to the disabled or the depressed. “This isn’t choice: it’s pressure; it’s not mercy: it’s abandonment.” He urged the Church to defend life for the sick, the hurting, and the unseen.

The Interim Bishop of Liverpool, the Rt Revd Ruth Worsley, spoke of sharing special moments with people at the end of their lives who received compassionate care in hospices and from family. Even in the NHS, people saw the immense value of spiritual care provided by chaplains and were increasing funding for them, she said. She urged members to support the motion and demand more money for, and universal access to, palliative-care services.

Dr Angus Goudie (Durham) suggested that there was “no real choice” between a fully funded assisted-dying service and a “patchily funded” palliative-care service. There was a danger of “scope creep”, which could change society in ways that few wanted, but that were, he said, impossible to reverse. If a hospice could not opt out of any future assisted-suicide system, it would see its entire ethic destroyed, he said.

Summing up, Bishop Mullally said: “This debate can shape society and our nation. I remain deeply concerned about this legislation and its possible impact on the most vulnerable.” She pledged to engage with the Bill when it reached the House of Lords, and encouraged members to pray for peers.

The motion was carried by 238-7, with seven recorded abstentions. It read:

That this Synod, in light of recent debates on the Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill, reaffirm that every person is of immeasurable and irreducible value, and request His Majesty’s Government work to improve funding and access to desperately needed palliative care services instead of enacting a law that puts the most vulnerable at risk.

Bishop Mullally led a prayer for those who “sit in the shadow of death and those who sit with them”.

Read more reports from the General Synod digest here