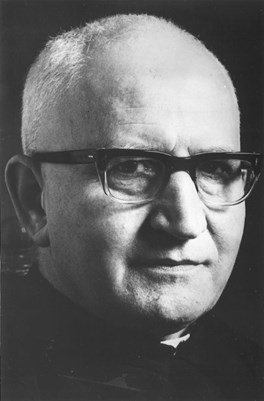

CHRISTOPHER BUTLER, monk, abbot, bishop, theologian, and ecumenist, is a fascinating example of an Anglican who became a Roman Catholic but never forgot or despised his classical Oxonian education, his Anglo-Catholic roots, and his lasting debt to Anglican scholarship.

To this he added his own distinctive contribution to the Second Vatican Council, first as an abbot and then as a bishop, and he became the chief exponent and champion of the Council in the somewhat unappreciative world of post-Vatican II English Roman Catholicism.

Peter Phillips excellently highlights Butler’s early call to the cloister, as well as his Keble achievements and his significant revisionist endeavours as Abbot of Downside. In the latter, he owed much to Dom David Knowles. He was already engaged in ecumenical discussions, and so encouraged his somewhat reluctant co-religionists. He became a well-known apologist for Christianity, bringing intelligence to arguments for faith.

Theologically, he was deeply influenced by Newman on development and by the Jesuit Bernard Lonergan philosophically. He continually asked questions and was in a philosophical dialogue with atheism. His spirituality was accordingly the via negativa, and he often re-read The Cloud of Unknowing.

Christopher Butler OSB

Christopher Butler OSB

Butler wrote many books and articles, but his own “conversion” to Vatican II was the inspiration for some of his major writings, not least The Theology of Vatican II (1967). Butler had known and become friends with the “influencers” at the Council, whether bishops or periti. Phillips is here and throughout the book able to draw on Butler’s considerable correspondence, not least with his brother (an Anglican priest in Canada) and his sister. There is, in consequence, a considerable Butler archive in Durham University. Thanks must go to Professor Paul Murray, who encouraged Phillips to write this very detailed and fascinating story.

Butler’s correspondence includes his regular doubts about the (then) ecumenical commitment of the English and Welsh hierarchy, including his reservations about Humanae Vitae (Paul VI’s encyclical on contraception) as well as his doubts about the (then) Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith and the influence of Roman conservatives. The letters also show his own theological development and changing positions, of which he was not ashamed. Butler was, furthermore, a considerable New Testament scholar and had no problem citing Protestant scholars, whether he agreed or not with their conclusions. Originally in favour of the priority of St Matthew’s Gospel, he later came to question his earlier conclusions.

This is not only a fascinating biography: the several chapters on Vatican II and on his part in the first Anglican-Roman Catholic International Commission (ARCIC I), including the details of sub-commission meetings, should make this book compelling reading for both ecumenists and Vatican II pilgrims. A couple of minor repetitions deserved better sub-editing, and one citation of Canon William Purdy makes him Director of the Anglican Centre in Rome, whereas a second correctly describes him as of the Vatican Secretariat for Promoting Christian Unity.

The book is haunted, throughout, by the tension between his conviction that the unity of the visible Church was indissoluble — his reason for “crossing the Tiber” — and the conviction of the Anglican Patristic scholar Stanley Greenslade that schism could be within the Great Church. Here, Butler may not have really faced up to the problem, on his view, of the Orthodox and Oriental Orthodox Churches recognised by Rome as true Churches but not in full communion. The problem remains. Butler was also deeply pastoral to those in trouble.

The Rt Revd Christopher Hill is a former Bishop of Guildford and was, among other things, Anglican Secretary of ARCIC I.

Christopher Butler: Monk, theologian, bishop

Peter Phillips

Weldon Press £30*

(978-0-9955853-5-5)

*obtainable from douaiabbey.org.uk