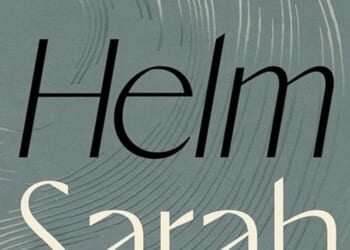

The England team for the tour of Australia in 1882-83; Ivo Bligh is seated, centre (Image: Popperfoto via Getty)

The tension in the packed crowd of 20,000 people at the Oval cricket ground that afternoon in August 1882 was almost unbearable. As England inched with agonising slowness towards the modest target set by Australia, the pressure became too much for some spectators. One man reportedly died of a heart attack, while another chewed right through the handle of his umbrella.

The strain also told on the England batsmen, who kept losing wickets at regular intervals, most of them to Frederick Spofforth, the Australian bowler known as “The Demon” for his unrelenting hostility. “Spofforth was no bowler; he was a hypnotist,” said England player Billy Barnes. Dismissed for 77, the hosts fell short by just seven runs.

As the cricket writer Tim Wigmore recounts in his monumental new history of Test cricket, this episode turned out to be a moment of destiny for the sport. England and Australia had been playing Test matches since March 1877, but the Oval humiliation was the national side’s first home defeat by any visiting team from Down Under. The result sent a shockwave through the sports-loving British public.

Satirising this mood of despair, a boozy, irreverent journalist called Reginald Shirley Brooks, who worked on The Sporting Times, wrote a mock obituary for the game which read: “In affectionate remembrance of English cricket which died at the Oval on August 29, 1882. Deeply lamented by a large circle of friends and acquaintances. RIP. NB: The body will be cremated and the ashes taken to Australia.”

Brooks’s choice of words showed that, as well as making fun of the hysteria over England’s defeat, he also wanted to highlight a political message about cremation, which in 1882 was still illegal in Britain. Both Brooks and his father were powerful campaigners for the practice – though neither of them lived to see its legalisation in 1902.

But the joke about the death of English cricket had a far more immediate impact. That winter a representative England team, led by the aristocrat Ivo Bligh, embarked on a tour of Australia. In the wake of the Oval defeat, Bligh light-heartedly declared that he was on a “quest for the Ashes”.

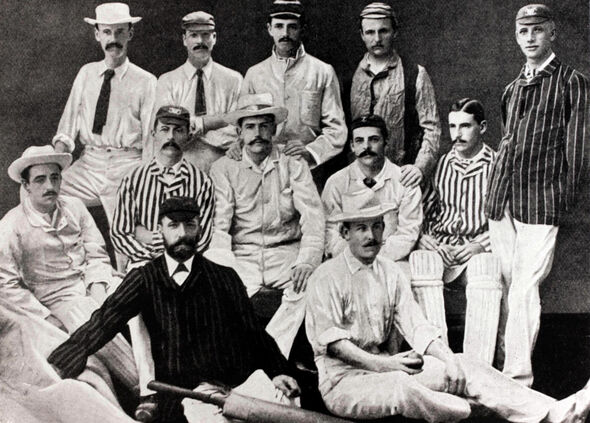

A replica of ‘The Ashes’ urn on display at Lords in London (Image: Getty)

The jocular theme continued after Bligh’s team had won the series, a victory which prompted a trio of young ladies in Melbourne to present him with the tiny, terracotta urn that reportedly contained the ashes of a burnt cricket bail. So was the great sporting tradition born that endures to this day.

Bligh brought home not only the Ashes but also a bride, Florence Morphy, who had worked as a governess in Melbourne and was the leader of the trio that presented Bligh with the urn. Having been instantly smitten, Bligh became the only England captain to have made – and had accepted – a proposal of marriage during a Test match!

“A more truly lovable character I never met,” he wrote to his parents of his bride-to-be. Later in their marriage, she became a successful romantic novelist. Since her husband’s victory, the duel between England and Australia has become one of the most prestigious in international sport, with a unique, rich heritage that is matched by the ferocity of the competition.

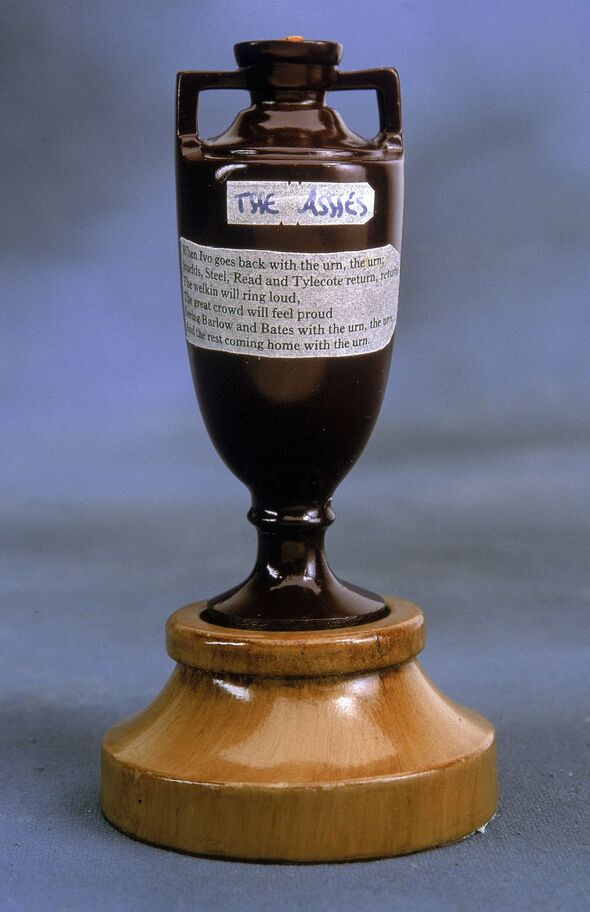

During a match in 1989, exhausted England batsman Robin Smith asked if a drink could be brought out to him. “No! What do you think this is, a f****** tea party,” said the tough-minded Australian captain Allan Border.

More recently, at Lord’s in 2023, there was a storm of controversy over the stumping of England batsman Jonny Bairstow, who had wandered out of his crease, thinking the ball was dead. To many angry critics, the Aussies’ actions breached the ethics, if not the laws of the game.

But this incident pales beside the Ashes’s most explosive row, which detonated in the 1932/33 series when England’s austere, ruthless captain Douglas Jardine used his battery of fast bowlers, led by Harold Larwood, to intimidate the Australian batting line-up with persistent short-pitched bowling.

The chief aim was to halt the flow of runs from the prolific young Australian Don Bradman, the greatest batsman the world has ever seen. Jardine’s tactics worked. England won the series as Bradman was reduced to the status of a mere mortal. But the triumph came at a tremendous cost. After two Australians were felled by dangerous bouncers, the England team was accused of “unsportsmanlike” behaviour and diplomatic relations between the two countries were almost broken off.

Florence Rose Morphy who became the Hon Mrs Ivo Bligh after winning English batsman’s heart (Image: Unknown)

When Rockley Wilson, one of Jardine’s former teachers at Winchester, was told of the decision to put him in charge of the 1932/33 tour, he said presciently: “He’ll win back the Ashes but he could lose an Empire.”

This week sees the resumption of the Ashes rivalry as the First Test in this winter’s series began in Perth overnight [NOV 20/21]. It will be a tough fight for England, given that Australia have long seemed almost invincible at home. Over the last 35 years, England have been victorious in just one tour, that in 2010/11, and during that time they have suffered two whitewashes: in 2006/7 and 2013/4.

Despite that sorry record, unprecedented numbers of England supporters will journey to Australia this winter. The Barmy Army, the official organisers of travel for England fans, have sold 40,000 packages for the 2025/6 series – three times more than in 2017/18. Excited anticipation is particularly strong for this series because of England’s entertaining style – known as “Bazball” – which puts a premium on aggressive batting and has been developed by the skipper Ben Stokes in tandem with the coach Brendon McCullum.

Shane Warne in action against England at Lord’s in 2005 (Image: Getty)

For decades, pessimists have been predicting the slow death of cricket, especially the five-day Test version, yet the game is in rude good health, bolstered by the riches of the Indian Premier League and the lucrative sales of broadcasting rights. It’s important that Anglo-Australian cricket thrives, because the sport is part of our shared cultural landscape. Its passions are woven into the fabric of our history; its dramas have shaped relations between the two democracies.

The sense of pride engendered in Australia by early victories over England was a vital force in building the spirit of nationhood in the new country, which only came formally into existence in 1901 when the six separate colonies were brought together in a self-governing federation. Similarly, in the late Victorian age, cricket became not just England’s national sport, but also a metaphor for the highest moral values in our national character, reflected in phrases like “it’s not cricket” a “playing a straight bat”.

Just as the late Shane Warne, the greatest leg-spin bowler of all time, encapsulated several key Australian traits such as exuberance, indefatigability, determination and self-belief, so England’s finest ever batsman, Sir Jack Hobbs, was often said to embody the classic British qualities of decency, reserve, modesty and restraint.

Australia Captain Steve Smith, left, and Ben Stokes prepare for the Ashes (Image: PA)

In an essay written in 1931, the left-wing Labour politician Harold Laski wrote that: “Hobbs is the typical Englishman of legend. You would never suspect from meeting him that he is an extraordinary person. He never boasts about himself. He gets on with the job quietly, simply, efficiently.”

Both Hobbs and Warne feature prominently in Tim Wigmore’s epic history. Although he first played Tests as long ago as 1907, Hobbs remains to this day the heaviest run scorer for England in the Ashes, while Warne – who sadly died in 2022 aged just 52 – is still the greatest wicket taker in Ashes history.

In a typically vivid passage in his book, Wigmore describes how Warne burst onto the scene in 1993 at Old Trafford, Manchester, where he made his debut against England. Coming on to bowl on the second afternoon of the match, his very first delivery was a piece of mesmerising wizardry which fizzed through the air towards the England batman Mike Gatting. Then on landing it turned viciously from the legside, leapt past Gatting’s groping bat and crashed into the top of his off-stump.

Barely able to grasp what he had witnessed, Gatting trudged back to the pavilion with a bewildered expression on his face.

“The Ball of the century”, as it became known, heralded both the revival of leg-spin, cricket’s most captivating art and the continued mastery of Australia in the Ashes, which was not broken until Michael Vaughan led England to victory in the 2005 encounter, now universally regarded as one of the greatest series.

Australia captain Allan Border with the Ashes and a celebratory beer after sixth test in 1989 (Image: Getty)

During almost 150 years of Test cricket, as Wigmore’s massively-researched book shows, Australia and England have almost been evenly matched, the former winning 34 series to the latter’s 32. Australia’s recent superiority at home is counter-balanced by a host of outstanding performances by England, such as the victory at Headingley in 2019 when Ben Stokes, staring defeat in the face and with the last man at the crease, smashed his way to the target. It was another miracle at Headingley, like the 1981 Test, when Ian Botham, batting with the tail, hit 149, then Bob Willis, bowling like the wind, took eight for 43.

From Geoff Boycott to Don Bradman, the cavalcade of sporting brilliance has always kept on rolling. This winter is a chance for new heroes to write themselves into the record books and established stars to confirm their greatness.

- Test Cricket: A History, by Tim Wigmore (Quercus, £30) is out now

Test Cricket: A History, by Tim Wigmore is out now (Image: Quercus)