Back to basics

THE New Year brought an invitation to the “50th Anniversary Gathering” of those who matriculated at my Cambridge college in 1976: can it really be half a century since we all arrived in the fens, quivering with Tiggerish enthusiasm for a new and more grown-up life? A group of old friends plan to be there, and my wife has said that she will come, too.

In my last year, I had rooms in the college’s Great Court, one of the most beautiful spaces in Europe. Misty-eyed with memories of its gently plashing fountain, I booked us into college for the night.

A polite note came back to remind me that the rooms were single occupancy (so I would need two, not one) and probably much as I remember them. I am sure that Fiona will be seduced by a view that has not changed much since James I was on the throne, but will she feel the same about plumbing that dates from roughly the same period, with a hike up the staircase to the loo, and an open-air trek to the bathroom?

For this relief. . .

THE days between the final delivery of a manuscript and its publication in book form are usually halcyon; the hard work is done, and all that remains is a sweet sense of expectation as you wait to feel the weight of the first hardback copy in your hand.

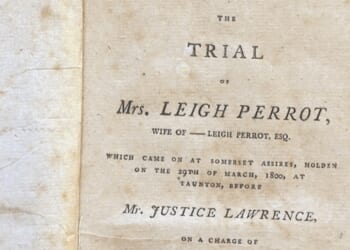

If your subject has current relevance, however, there is always the danger that events will date the book before it even rolls off the presses. My Made in America: The dark history that led to Donald Trump has seemed especially vulnerable because of the title character’s habit of inspiring often quite unexpected headlines. It has been an anxious few weeks.

I have argued that, far from being a maverick, or in some way “un-American”, the 45th and 47th President of the United States is as American as apple pie; there are precedents in American history for almost everything that he has done. Just before Christmas, he appointed a new envoy to Greenland, restating his view that the vast Arctic island was necessary for the “national protection” of the United States, and that “we have to have it.”

This idea goes back at least as far as the 1860s, when it was championed by William H. Seward, the Secretary of State who bought Alaska in the kind of sensational real-estate deal that the President admires. So far, so good; but the seizing of the Venezuelan leader Nicolás Maduro (News, 9 January) caught me on the hop (as it appears to have done to most observers).

Then I remembered that, at the end of the 1835-36 War of Texan Independence, the American rebels took the Mexican leader Antonio López de Santa Anna prisoner and, before releasing him, forced him to give up his claims on the territory — an incident that I cover in Chapter 2. It is not an exact parallel, but it helps to provide the context for more recent events.

The book is out this week (to mark the anniversary of President Trump’s second inauguration); so, “Phew!”

Time travel

CHEMOTHERAPY is not nearly as brutal as it used to be. I am in the middle of a six-month treatment (the latest front in a decade-long battle with prostate cancer) and have suffered none of the nausea that used to be a side effect. It does, however, bring moments of deep exhaustion and lassitude, when even reading a serious book is a challenge; so I am experimenting with children’s books that I once loved.

Rudyard Kipling’s Puck of Pook’s Hill tells the story of a brother and sister who act out the Rude Mechanicals scene in Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream in a Sussex fairy ring; they are so pleased with their performance that they repeat it three times, and thus conjure the presence of Puck, “the oldest Old Thing in England”.

Puck introduces them to a series of characters who help them to understand the history of their country. At the end, the children sing: “Land of our Birth, our faith, our pride For whose dear sake our fathers died; Oh, Motherland, we pledge to thee Head, heart, and hand through the years to be!”

Kipling wrote the book while living in the Sussex village of Burwash, a place that, as a child, I often visited, as it was the home of two of my father’s elderly maiden aunts (they were the very model of that old-fashioned term). I loved reading it, partly because it fed the sense of that corner of England as a place of a deep and magical past, where the divide between the natural and supernatural worlds is paper-thin.

Some of that came back, but I could not entirely escape today’s headlines as I read. Kipling is sometimes accused of chauvinism, but almost all the characters whom Puck produces are foreign-born: they include Weland, smith to the gods in old German lore, who arrived with marauding Vikings; an assortment of invading Norman knights and barons; and a legionnaire defending the Roman Empire on Hadrian’s Wall.

Even more surprising — in light of the way Christianity has become part of the debate about national identity — is the almost complete absence of religion in the story. The Reformation gets the thumbs-down because it frightened all the fairies off to France, but that’s about it — apart, that is, from this brilliantly succinct piece of history: “Turkeys, heresy, hops, and beer Came into England all in one year.”

The first turkeys from the Americas are thought to have arrived here in the 1520s: one version has a Yorkshireman selling them in Bristol in 1526. The Pope turned down Henry VIII’s request for the annulment of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon in 1527; so the Protestant “heresy” (if this newspaper will forgive the phrase) did indeed arguably begin then, too. Flemish farmers began growing hops commercially in Kent in the 1520s; their newly flavoured and more easily preserved beer soon trumped old-fashioned English ale.

There is a further link between these events: the Roman Catholic Church had a monopoly on gruit, the herb mixture used to flavour ale, and lost money and influence with beer-drinkers’ change of taste. What a lot of history in two lines.

Free flight

A VERY old friend lost both his father and his mother-in-law on the same day before Christmas. This melancholy overture to the feast was in part mitigated by the manner of his father’s death.

J (I use only one of his initials to protect his identity) had been a keen pilot; he owned and flew an Auster, a tree-hopping Second World War spotter plane, well into his eighties. He became seriously ill this autumn, and, in mid-December, his children were advised that they should say goodbye. When they gathered, they found him unconscious, but still living.

One of his daughters — herself a qualified pilot — decided to take him through the preparations for take-off one last time: “Throttle, open at a half-inch. . . Master switch, on. . . Flaps, up. . . Prop, clear,” etc. She ended with: “OK, Dada, brakes are off, and off we go. . . Stick, back. . . We are up!” At which point, her father squeezed her hand, smiled, and died.

Edward Stourton is an author and broadcaster. He presents Sunday on Radio 4.

Made in America: The dark history that led to Donald Trump is published by Torva at £20 (Church Times Bookshop £18); 978-1-911742-11-1.