Reader Patti Kruse wrote us a few years ago asking us to persist in our annual remembrance of the D-Day landings on the Normandy beaches. “My dad landed on Omaha Beach on D-Day,” she told us. “He was one of the fortunate ones, as he was never physically injured and managed to survive from D-Day all the way through the Battle of the Bulge and V-E Day. He rarely spoke about his experience except to say how much he loved America and was grateful to have served (he had immigrated from Ireland as a very young man).”

Reader Patti Kruse wrote us a few years ago asking us to persist in our annual remembrance of the D-Day landings on the Normandy beaches. “My dad landed on Omaha Beach on D-Day,” she told us. “He was one of the fortunate ones, as he was never physically injured and managed to survive from D-Day all the way through the Battle of the Bulge and V-E Day. He rarely spoke about his experience except to say how much he loved America and was grateful to have served (he had immigrated from Ireland as a very young man).”

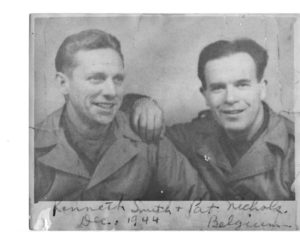

She added: “I’ve attached a picture of my dad (Pat Nichols, at right in the photo above) taken somewhere in Belgium December 1944 during the Battle of the Bulge. I asked him once about the picture and he said they were told, ‘Only Yanks would be crazy enough to take their picture during the Battle of the Bulge.’ He loved being called a Yank, especially as he used to be teased about his magnificent Irish brogue.” Here is our annual post in observation of the anniversary of D-Day, with a salute once again to Patti’s dad as representative of all the brave Americans who did their duty that day:

Eighty years ago today our fellow Americans and their allies stormed the beaches of Normandy to vanquish the Nazis’ supposed thousand-year regime. In his D-Day message to the troops, General Eisenhower declared: “We accept nothing less than full victory!”

The landing was necessary if the war was to be won. In 1984 President Reagan called it “a giant undertaking unparalleled in human history.” Yet success was far from assured. Eisenhower tucked a second message away to use in case of failure: “Our landings in the Cherbourg-Havre area have failed to gain a satisfactory foothold and I have withdrawn the troops. My decision to attack at this time and place was based upon the best information available. The troops, the air and the Navy did all that Bravery and devotion to duty could do. If any blame or fault attaches to the attempt it is mine alone.”

We seek to remember the fallen and honor all those who did their duty that day. They performed fearsome tasks with awe-inspiring fortitude.

In his 2004 Wall Street Journal column “Too much, too late,” Professor David Gelernter expressed his revulsion over “the tidal wave of phoniness” that he detected in the celebration of “the greatest generation” by the boomer crowd. That particular tidal wave may have receded, but his remedy abides. As a remedy for the phoniness he detected, Professor Gelernter prescribed teaching to our children the major battles of the war, the bestiality of the Japanese, the attitude of the intellectuals, and the memoirs and recollections of the veterans.

Following Professor Gelernter’s prescription, I have worked my way through Rick Atkinson’s The Guns At Last Light: The War in Western Europe, 1944-45, the concluding volume of Atkinson’s brilliant Liberation Trilogy. In recent years I read the late Dartmouth English Professor Harold Bond’s moving Return to Cassino. E.B. Sledge’s With the Old Breed: At Peleliu and Okinawa is the classic memoir of combat in the Pacific theater that should be on everyone’s list (the Oxford paperback edition includes an introduction by Paul Fussell).

Professor Gelernter failed to assign a paper topic for his proposed course. I would assign an essay on the subject of sacrifice. Do we deserve the sacrifice made on our behalf? What we can do to make ourselves worthy of it?

The battle of Omaha Beach of course represents only a part of Operation Neptune and the other battles that occurred on the Normandy beaches. The story of Omaha Beach is nevertheless deserving of special recognition.

S.L.A. Marshall was commissioned to serve as a combat historian with the Army in World War II. By 1960, he was already concerned that “the passing of the years and the retelling of the story have softened the horror of Omaha Beach on D Day.” That year the Atlantic Monthly published Marshall’s essay on Omaha Beach based on the field notes he had compiled during his service as combat historian. The essay — “First wave at Omaha Beach” — is available online. Marshall’s essay was the original source for some of the telling details that Stephen Ambrose memorialized in his book on D-Day.

In 2019 the Library of American published Cornelius Ryan’s classic The Longest Day together with A Bridge Too Far and other of Ryan’s World War II writings, edited and with an introduction by Rick Atkinson. Ryan went to heroic lengths to compile the recollections of every D-Day survivor he could find. Atkinson writes that Ryan’s “meticulous research and taut narrative revived public interest in one of the most extraordinary events of the twentieth century.” Winston Groom’s moving Wall Street Journal review brought the Library of America edition of Ryan’s classics to my attention.

Let us read the books, pass them on to our kids, and keep the history alive in the course Professor Gelernter has prescribed. (First posted in 2004, slightly revised and updated in 2013, 2014, 2017, & 2024.)