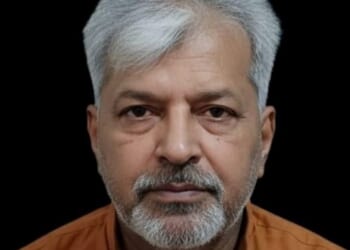

VATICAN CITY (LifeSiteNews) — Pope Leo XIV appointed Father Cyril Buhayan Villareal as the new bishop of Kalibo in the Philippines, drawing renewed attention to unorthodox theological positions he defended in an academic thesis on marriage and sexuality.

On January 24, Pope Leo XIV appointed Villareal as bishop of the Diocese of Kalibo, located in the central Philippines. The decision has drawn attention over Villareal’s previous academic work in moral theology, in which the new bishop questioned the natural law framework underpinning the Church’s traditional teaching on marriage, sexuality, and contraception.

READ: New Vienna archbishop’s consecration Mass features women in key roles, altered rituals

In his 2011 academic work submitted to the University of Vienna, Villareal wrote that he intended to present “a new way of looking at sexual morality through the Trinitarian love and not anymore through the natural law perspective.”

In the introduction to his thesis, Villareal explains that the work is divided into two parts. While the first part presents what he calls “the orthodox teachings of the Church on marriage and sexuality,” the second part elaborates upon “an opposite view from that which the Church upholds.” He states that the overall aim is to arrive at “a more integrated view of sexuality and marriage” by juxtaposing these perspectives.

In doing so, he presents moral reasoning that departs from the classical Catholic moral framework, grounded in natural law and reaffirmed in magisterial documents such as Humanae Vitae by Pope Paul VI, which teaches the intrinsic immorality of artificial contraception.

The thesis acknowledges that the official teaching of the Church “establishes a close bond between sexuality and procreation and then links the two in matrimony,” highlighting “the inseparability of the unitive and procreative aspects of the marital act” as its foundation in natural law. Villareal nevertheless raises the question of whether “the morality of the sexual relation of the spouses in marriage” might be determined “in a new way” so that the Church’s position could be “better understood and accepted.”

Villareal thus seeks to reconcile proportionalist moral theology – a controversial current within contemporary Catholic moral theology – with the classical Catholic moral tradition.

Proportionalist moral theology evaluates the morality of human acts by weighing the proportion of goods and evils anticipated in concrete circumstances. Rather than judging actions according to intrinsic moral norms derived from natural law, proportionalism assesses whether a given choice produces a greater balance of positive values over negative consequences. In this framework, moral absolutes are not denied explicitly but are functionally subordinated to contextual evaluation.

This approach is incompatible with the official moral teaching of the Catholic Church, which affirms that certain acts are intrinsically evil and may never be chosen, regardless of intention or circumstances. The Catechism of the Catholic Church relates that “there are acts which, in and of themselves, independently of circumstances and intentions, are always gravely illicit” (CCC, no. 1756). This principle is foundational to Catholic moral reasoning.

The Church’s teaching on contraception is a clear application of this doctrine. In Humanae Vitae, Pope Paul VI states that “each and every marital act must of necessity retain its intrinsic relationship to the procreation of human life” (cf. n. 11), and concludes that any action which – either in anticipation of the conjugal act or in its accomplishment, or in the development of its natural consequences – proposes, whether as an end or as a means, to render procreation impossible is “intrinsically wrong” (cf. n. 14).

In particular, Paul VI taught that it is not valid “to argue, as a justification for sexual intercourse which is deliberately contraceptive, that a lesser evil is to be preferred to a greater one.”

READ: Pope Leo says different Christian faiths are ‘already one’

Villareal presents proportionalist arguments for contraception which take into account the totality of goods pursued within marriage, rather than excluding the practice a priori as intrinsically immoral (pp. 108–112). Within this framework, artificial contraception is discussed not primarily as an act defined by its moral object, but as a choice whose morality depends on proportional reasoning related to marital love, responsibility, and lived experience.

The incompatibility lies not merely in pastoral emphasis, but in the underlying moral criterion itself: proportionalism replaces the Church’s doctrine of intrinsic moral evil with a consequentialist mode of evaluation that the Magisterium has consistently rejected.

Villareal’s episcopal appointment comes amid a broader pattern of recent nominations that have attracted attention within the Catholic world. In recent months, Pope Leo XIV has appointed several bishops whose prior statements or theological positions have stood at odds with Tradition. These include Shane Mackinlay in Brisbane, Australia; Beat Grögli in St. Gallen, Switzerland; José Antonio Satué Huerto in Málaga, Spain; Sithembele Sipuka in Cape Town, South Africa; and Joseph Grünwidl in Vienna, Austria.