A short excerpt from today’s >17K-word decision by Judge Sarah Russell (D. Conn.) in Arroyo-Castro v. Gasper:

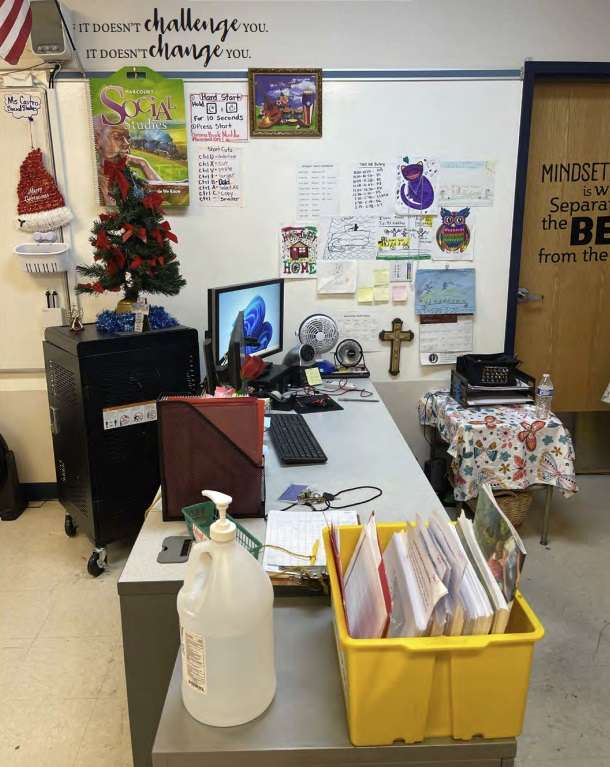

The dispute centers around whether Ms. Castro [a New Britain schoolteacher] has the right to affix an approximately foot-high crucifix to the wall near the teacher’s desk in a classroom of a public middle school….

The parties do not dispute that the crucifix display on the classroom wall is “speech” within the meaning of the First Amendment. At issue is whether the crucifix display is protected speech. When “a public employee speaks ‘pursuant to [his or her] official duties,’ … the Free Speech Clause generally will not shield the individual from an employer’s control and discipline because that kind of speech is—for constitutional purposes at least—the government’s own speech.” Kennedy v. Bremerton Sch. Dist. (2022) (quoting Garcetti v. Ceballos (2006)). Here, Ms. Castro’s job duties specifically included decorating the classroom walls to make the physical classroom environment conducive to student learning. Under these circumstances, based on the existing evidentiary record, I conclude that Ms. Castro acted pursuant to her official duties when she posted items on the classroom wall that students would see during instructional time.

The classroom wall decorations are thus speech pursuant to Ms. Castro’s official duties and subject to the District’s control. For these reasons, I conclude that Ms. Castro is unlikely to prevail on the merits of her free speech and free exercise claims and is not entitled to the extraordinary remedy of a preliminary injunction….

Recall that the First Amendment protects a government employee’s speech from being restricted by the employer if

- the speech is said by the employer as a private citizen, and not said as part of the employee’s job duties, Garcetti v. Ceballos (2006), and

- the speech is on a matter of public concern, Connick v. Myers (1983), and

- the damage caused by the speech to the efficiency of the government agency’s operation does not outweigh the value of the speech to the employee and the public, Pickering v. Bd. of Ed. (1968).

The court’s analysis is focused on why element 1 comes out against Castro.

Here, by the way, is an excerpt of the court’s conclusion that the Free Exercise Clause analysis here is the same as the Free Speech Clause analysis:

Kennedy does not address the issue directly but implies step one of the Pickering- Garcetti framework applies at least in some form to free exercise claims, stating: “Because our analysis and the parties’ concessions lead to the conclusion that Mr. Kennedy’s prayer constituted private speech on a matter of public concern, we do not decide whether the Free Exercise Clause may sometimes demand a different analysis at the first step of the Pickering-Garcetti framework.” Justice Thomas’s concurrence in Kennedy observes that the “Court refrains from deciding whether or how public employees’ rights under the Free Exercise Clause may or may not be different from those enjoyed by the general public.” Justice Thomas stated: “In the free-speech context, for example, that inquiry has prompted us to distinguish between different kinds of speech; we have held that ‘the First Amendment protects public employee speech only when it falls within the core of First Amendment protection—speech on matters of public concern.’ It remains an open question, however, if a similar analysis can or should apply to free-exercise claims in light of the ‘history’ and ‘tradition’ of the Free Exercise Clause.” …

Ms. Castro’s free exercise and free speech claims fully overlap in the sense that the religious exercise that Ms. Castro says is infringed is necessarily communicative. Ms. Castro acknowledges that the crucifix display intended to convey a “particularized message.” She also states that she “sincerely believes that her religion compels her to display her crucifix, not hide it under her desktop” and “[s]tifling her religious expression through concealment of the crucifix ‘would be an affront to [her] faith.'” …

Given that Ms. Castro’s free exercise claim rests on exercise that necessarily involves communication of a religious message, I conclude that the analysis utilized under Pickering-Garcetti step one for Ms. Castro’s free speech claim applies to her free exercise claim. I have already concluded that the crucifix display on the classroom wall was pursuant to Ms. Castro’s official duties and is therefore speech attributed to the District. The speech is thus, for constitutional purposes, the government’s own speech. See Kennedy (“If a public employee speaks ‘pursuant to [his or her] official duties,’ this Court has said the Free Speech Clause generally will not shield the individual from an employer’s control and discipline because that kind of speech is—for constitutional purposes at least—the government’s own speech.”). Under these circumstances, the Free Exercise Clause does not compel the District to communicate a religious message. Rather, the District can control the messages broadcast to students on the classroom walls during instructional time.

Generally seems correct to me.