WHILE both ordained ministers hale from Northern Ireland, the Revd Duncan Hegan and the Revd Dr Jonathan Black operate in very different spheres. Fr Hegan is an assistant curate at St Alban the Martyr, Holborn, a traditionalist Anglo-Catholic parish in central London. Dr Black is a Pentecostal theologian, currently serving as Principal of the Apostolic Church Theology School and worshipping in a Welsh village near Bridgend. A phenomenon reported by both is an increase in unchurched young men coming to faith.

JONATHAN BLACKThe Revd Dr Jonathan Black

JONATHAN BLACKThe Revd Dr Jonathan Black

They are, Dr Black says, “just turning up out of the blue, in really quite unusual ways”. In some instances, people have arrived having had a dream. Others have arrived “randomly” at prayer and fasting meetings and found faith. He is hearing similar stories further afield in his denomination, the Apostolic Church UK, where the numbers baptised in just one month — April — equated to 30 per cent of the total for the entire previous year. In his local church in the past 15 months, 50 people have been baptised, many of them men from completely unchurched backgrounds.

Meanwhile, in his Victorian church in Holborn, Fr Hegan has seen a new mass for students and young adults grow in the past year from just six to 40, while Fidelium, a lay-led network of young Anglo-Catholics aged 18 to 35, attracts a diverse mix of people to both services and social events. Hostility to Christianity is, he suggests “the preserve of Boomers”.

FOR those familiar with the Bible Society’s Quiet Revival report, the two accounts put flesh on raw data (News, 8 April). Published in April, and drawing on a YouGov poll of 13,000 adults, the report announced that “something amazing” was happening in the UK, “challenging long-held predictions about the future of Christianity in the twenty-first century”.

It suggested a rise in church attendance among 18- to 24-year-olds from four per cent in 2018 to 16 per cent — rising to 21 per cent among young men. Young adults aged 18 to 24 were “more spiritually engaged than any other living generation”, with the highest rates of belief in God and regular prayer.

Also heralded was a “transformation in terms of denominational affiliation”. Among 18-34s, only 20 per cent of churchgoers were Anglican (down from 30 per cent in 2018): 41 per cent were Roman Catholic, and 18 per cent were Pentecostal.

The numbers have attracted scepticism. David Voas, Emeritus Professor of Social Science in the UCL Social Research Institute, has described the study’s findings as “wholly unbelievable” and “wildly out of step with wider figures”, including the churches’ own counting of attendance, including the C of E’s carefully collected Statistics for Mission (Features, 23 May).

The annual British Social Attitudes survey found that the share of adults in England and Wales who said that they were Christian and went to church at least monthly fell from 12.2 to 9.3 per cent between 2018 and 2023. It is not only the size of a sample, but how representative it is, that matters.

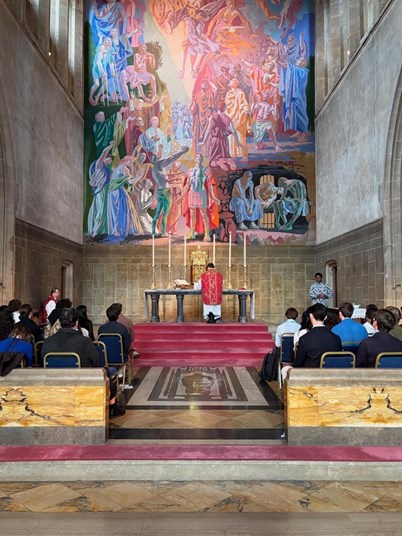

DUNCAN HEGANA recent mass for students and young adults at St Alban’s, Holborn, with 36 in attendance

DUNCAN HEGANA recent mass for students and young adults at St Alban’s, Holborn, with 36 in attendance

Dr Clive Field has been working alongside Professor Voas since 2008 on the British Religion in Numbers project, an online religious-data resource for Great Britain, and shares his collaborator’s doubts. “As a historian who has been researching British religious statistics for the past half-century, and from the 18th century to the present day, I see little evidence that Britain is undergoing some kind of ‘religious revival’ in contemporary times,” he says. “So far as can be ascertained, denominational in-person attendance statistics have bounced back somewhat from the lows of the Covid-19 era, but remain below 2019 levels.”

In the April edition of Counting Religion in Britain, he warned that “self-certifying polls tend to encourage aspirational replies about religious identity and practice.”

Some clergy are similarly wary. The Rector of St Mary’s, Nantwich, the Revd Dr Mark Hart, a mathematician by training, has calculated that the study’s data on 18- to 24-year-olds would translate to about 180 in that bracket attending church in Nantwich once per month, across all churches. “It would be wonderful if true, but it’s out by a long way, and we’re not unusual. It may be argued that this high attendance is concentrated in certain areas, but it would need to be even higher there to give the same average.”

There is, however, he says “much to encourage” locally. At St Mary’s, there has been a “steady trickle” of adults attending church for the first time, and being baptised and confirmed, while the electoral roll has increased from 380 to 444 since 2019.

It is a phrase that has appeared elsewhere. Parish-level reports posted online during a recent Church House webinar on revival included a rise from five to 50 children over three years at St Thomas’s, Garstang, a “traditional church in a rural town in north-west England”, and a “steady trickle of new people spontaneously seeking faith, most of them under 30”, at Crofton Parish Church, in the diocese of Portsmouth.

THE director of research at the Bible Society and a co-author of Quiet Revival, Dr Rhiannon McAleer, is equanimous about the reaction to date. “We don’t mind critique or robust conversations. It makes us sharper and moves everyone forward.”

When it comes to the disparity between surveys and the Church’s own counts — the C of E’s Statistics for Mission, for example — she notes that they “very rarely” align, partly because counting is “incredibly difficult”. Practising Anglicans make up a tiny proportion of the population, she says: a small margin of error equates to large numbers. But the data map well on to the latest census, in terms of its religious demographics. “We’ve got this more active Christian segment among young people, but a much smaller nominal Christian dataset, which makes sense with everything else we know from really robust datasets.”

BIBLE SOCIETYDr Rhiannon McAleer

BIBLE SOCIETYDr Rhiannon McAleer

She warns against “a desire for easy answers”, however, to question what factors are at play. “It’s not the time to be too triumphalist. More people coming to church is not a return to the Christianity of the past. . . This is a new landscape. . . There has to be a posture of humility and learning, trying to work out what’s going on.”

When it comes to the C of E, with its disproportionately older congregations, “significant generational decline” remains on the horizon, she suggests, even if you factor in an increase in young people. A recent review of six rural mission projects, commissioned by Church House and carried out by Brendan Research, What’s In Our Hands, said that “demographics in deep rural areas mean that maintaining Sunday attendance numbers is growth in disguise and that ‘scaling up’ approaches with ambitious targets are unlikely to work.” One study suggested that “arresting decline” was a good enough definition of growth.

THE founder of Brendan Research, Dr Fiona Tweedie, a former university lecturer in statistics, shares Dr McAleer’s excitement about Quiet Revival, but admits that her initial reaction “We’d love this to be true — but really?”

Looking at the Bible Society’s methodology was reassuring, she says, given the “very big sample” and “well-put” questions. But she remains conscious of “nuances”: those who chose to take part in a longer survey about religion will have self-selected. Standardising to more recent data about the ethnic make-up of the country may increase the number of people in the sample who are likelier to be Christian.

But her main point is about where you look when assessing the health of the Church. “If you are looking in the obvious places where you have always looked, because being a practising Christian in the UK means that you go to an established denomination regularly every Sunday . . . I don’t think you will see the increases that the report is reporting on,” she says.

It is possible that not everyone who considers themselves to be part of a church is being counted, she suggests. You need to be “noticed” by the person counting; many may not meet the “bar” for frequency of attendance.

She admires the way in which the Bible Society has invested in “asking everybody — not just the people who are in the Church that we see, looking out, but the people who are out there, looking in”. There is a theological aspect to this, she suggests. “God is at work in the world with all the people in England and Wales, not just the ones that are noticed to attend an established place of worship on a Sunday morning.” There are discrepancies, she acknowledges, “but I absolutely would not write this off at all.”

A RECENT report from Brendan Research suggested that attendance at Pentecostal diaspora churches in Scotland now matched that to be found in more established denominations; but the diaspora churches were hampered by a lack of understanding or support from the wider Church (News, 8 November 2024). This summer, the Christian communications agency Jersey Road suggested that the national media were failing to look beyond “traditional streams” of the Church (News, 4 July).

Dr McAleer says that she was disturbed to see her research “weaponised”, and the far Right picking up on it at some points: “We had made a particular point about trying not to make this about white nationalism, and pointing out the diversity of the Church and how significant this is for the future profile of the Church.” The polling suggests that one third of churchgoers aged 18 to 54 are from an ethnic minority. Close to half of the young Black people aged 18 to 34 surveyed reported attending church at least monthly. For his part, Dr Black says that waves of immigration had “transformed” the landscape of the Pentecostal Church. He learned recently that at a church at a small town in west Wales, 23 nationalities were represented.

JERSEY ROADThe Revd Nims Obunge addresses a recent Jersey Road conference “Faith in the Media”

JERSEY ROADThe Revd Nims Obunge addresses a recent Jersey Road conference “Faith in the Media”

In a recent Church House webinar exploring reports of revival, Dr McAleer spoke alongside the Revd Wole Agbaje, who leads IMPRINT church, which worships in St Clement Eastcheap, in the City of London. St Clement’s hosts four Sunday services, mainly attended by young people. Mr Agbaje grew up in the Pentecostal Church and believes that the current movement is helping to transcend denominational divisions.

It is a perspective shared by the Revd Nims Obunge, senior pastor of Freedom’s Ark, a Pentecostal church in north London. “We need to look at how we get to that moment where we are not restricted to church denominations, but the unity of the Church,” he says. “There is something powerful about when the Church becomes one.”

He currently chairs the board of trustees for Jesus House, the main London centre of the Redeemed Christian Church of God. At its recent event in Wembley Arena, a young person asked everyone present under 35 to hold up their phone with the torch on and wave them, prompting at least half of the 10,000 present to respond. “There was just a roar — it was electrifying,” he recalls. “You knew that there was a sense of each of them saying ‘We are here. There is something God is doing in this space.’”

A GREATER spiritual openness, and lack of hostility towards Christianity, among the youngest generation, has surfaced in other research. A YouGov survey reported that the percentage of 18-24s affirming a belief in God had risen from 16 per cent in 2021 to 45 per cent this January. That month, a OnePoll survey of 10,000 people, commissioned by the writer Christopher Gasson, found that only 13 per cent of the under-25s identified as atheist — the lowest of any generation.

At Fidelium, it is “very hard to generalise” about the demographics, Fr Hegan says. “A lot of these people are not stereotypical Anglo-Catholics. They are not wearing tweed jackets and ties. Some of them do, and that’s wonderful, but a lot of them are not.” Young professionals in banking, unemployed teenagers, and single mothers worship alongside transgender people, and Christians from India, America, Spain, and China.

People tend to come because of curiosity, or seeking community, he says. “An awful lot of people are lonely a lot of the time — and that applies to all ages.” Besides this, “whether they know it or not, a lot of young people are very disillusioned with the world and the culture and society they have grown up in.” Generation Z are seeking “something that’s not a performance. . . It’s mysterious. They don’t understand it.”

Young people have grown up in a “very unstable world”, he says. They “feel as though the world around them is very atomised; there is not much in the way of clear moral authority or moral teaching.” His advice to the Church if England is to show “confidence in what we are and what we are for. . . Make sure that you are saying the Office, and celebrating the eucharist, and offering the Church’s sacraments. This sends such a clear message to young people that we know what we are about.”

Flowing from confidence is the sense that “being a Christian is fun, and good, and good for your life,” he says. The biggest conduit to the Church is those already attending who invite their friends. “There are so many people out there who want to go to church, want to believe in Jesus, want to have a faith, but they just need to be invited.”

IN THE Roman Catholic Church, reports suggest that the Quiet Revival findings are reflected in the pews. In April, almost all English dioceses contacted by the Catholic News Agency reported a significant increase in both catechumens and candidates at the Rite of Election at the start of Lent, compared with last year.

Dr Peter Halsall, a layman in the diocese of Salford, began attending daily mass at St Mary and St Philip Neri, Radcliffe, in 2012, as part of a congregation of between eight and ten, most of whom have since died. There are now as many as 45, mostly older, retired people, about 40 per cent of whom are men. At each of the three Sunday masses, attendance stands at between 90 and 120, totalling about 500 monthly.

“I have looked up records of the parish in the 19th and 20th century, and numbers were higher, but not, in fact, that much higher,” he observes. Much of the increase has come from African, mostly Nigerian, families, as well as some from South India. Back in 2012, he recalls, about 90 per cent were “of the usual Manchester ring-town Catholics of Irish descent”. He found a recent Palm Sunday mass at the Birmingham Oratory “jammed, for a very traditional liturgy”. About one quarter of the congregation were men aged 20-45.

Charlotte Choley-Kovacevic, who looks after communications, social media, and events planning for Fidelium, joined the Church of England having been confirmed in the Roman Catholic Church. Now 21, she recalls growing up with “cringe atheist content” online. “It’s really unsatisfying; it’s not particularly edifying; and it actually leaves you quite hopeless. People are over it.” Both Pentecostal and Roman Catholic churches offer something that is “nothing like what you see in your day-to-day life”, she suggests.

AMONG the Quiet Revival datapoints that have attracted attention is an apparent shift in the gender balance, with young men overtaking women in Christian identity and churchgoing. This would buck a longstanding trend. In a 2010 article, “Where are the men?”, Dr Field noted that the cry could be heard back in the 18th century. “When the first large-scale census of churchgoing which controlled for gender was conducted, in inner and outer London in 1902-03, 61 per cent of worshippers were found to be women. At the 2005 English church census, the proportion was 57 per cent.”

The Bible Society’s report prompted Kristin Aune, Professor of Sociology of Religion at Coventry University, to dig into data that she has helped to collect about British students. Of 4500 students polled in 2022 (published as “Building Positive Relationships among University Students across Religion and Worldview”), 54 per cent of the female participants identified as “not religious”, compared with 40 per cent of the men. A total of 26 per cent of the women identified as Christian, compared with 39 per cent of the men.

Young men and young families are among the people with no church background “turning up on Sundays, turning to Christ, and turning their lives around”, according to reports received by Dr Ros Clarke, associate director at the Church Society. At St Mary Magdalene’s, Gorlestone, an estate church in Great Yarmouth, a young man was baptised earlier this year after a dream in which Jesus appeared. One father bought his whole family crosses after bringing them to church as a response to being questioned by his six-year-old daughter about life and death.

Further afield, other countries are reporting an increase in religiosity among young men. A study of confirmands in Finland co-led by Professor Professor Kati Tervo-Niemelä published earlier this year found that the percentage of young men confirmands who said they believed in God had grown from one third in 2019 to two-thirds in 2024 (News, 15 August).

Last year, the Survey Centre on American Life reported that 54 per cent of Generation Z adults who had left their formative religion were women. Women of this generation were also more likely to define as religiously unaffiliated than men. Last year, ABC News reported on the results of the Australian Community Survey, which found that 39 per cent of men in Generation Z identified as Christian, compared with 28 per cent of women of the same age group.

DATA and anecdote have prompted some to speculate about motive. “With Christian nationalism increasingly assertive in the United States, and the likes of Jordan Peterson and other pro-Christian influencers appealing to young men in particular, perhaps church attendance is seen as desirable by a growing minority of this demographic,” Humanists UK observed in a blog responding to the publication of Quiet Revival.

Some have connected the rise in religiosity to more conservative social and political views among young men. Last year, the Financial Times published a report — “A new global gender divide is emerging” — which said that women in the UK aged 18 to 30 were now 25 percentage points “more liberal” than their male contemporaries. YouGov reports that, at the last General Election, young men were twice as likely to vote Reform UK, and more likely to vote Conservative, than young women.

Among the male celebrities advocating Christianity are Russell Brand, currently facing rape and sexual-assault charges, and Dr Peterson, who has argued that men represent order because they are “the builders of towns and cities, the engineers, stonemasons, bricklayers, and lumberjacks, the operators of heavy machinery” while women represent chaos because of “the crushing force of sexual selection”.

DUNCAN HEGANA pub gathering after mass at St Alban’s, Holborn

DUNCAN HEGANA pub gathering after mass at St Alban’s, Holborn

The New York Times columnist Ross Douthat, a Roman Catholic and conservative, has described a “pessimistic scenario” in which young men are seeking “male-friendly refuges from what they perceive as an increasingly feminized and even misandrist liberal culture”, drawn to the very aspects that are alienating many young women from the churches of their upbringing. A more optimistic scenario would be that churches are “stabilizing and elevating men who are currently adrift and making them more appealing as potential spouses than any currently available force in either ‘normie’ or very online culture”.

Among articles with titles such as “Young women are leaving church in unprecedented numbers”, the tendency to analyse churchgoing among women in terms of its impact on others, or in contrast to young men — rather than on the women themselves — is striking. “Without this dedicated source of volunteer labour, many congregations will be unable to serve their membership and their communities,” a blog on the American Survey Center website observed. “What’s more, research finds that mothers play an instrumental role in passing on religious values and beliefs to their children.”

DISCUSSION about a revival among young men, and concern about possible drivers, have led Fr Hegan to question whether other demographics are regarded with the same sort of suspicion. “People very rarely come to church in the first instance for quote-unquote ‘right reasons’,” he observes. “Once they start going, they encounter Jesus, and that transforms their lives. . . We draw a majority young-male crowd because, if you are a young man in London, and you are at university and at work, this is one of the few places where people are really happy to see you. . . That’s enormously powerful for a lot of people.”

Professor Tervo-Niemelä reports that interviews with young men drawn to Christianity in Finland have uncovered a desire for stability and a clear moral framework in a fast-changing world, and a sense that “male voices are still heard and accepted within church circles”: that here you can be a “normal man”.

Dr Anne Richards, the C of E’s National Public Policy Adviser, who specialises in modern society, popular culture, contemporary spirituality, and apologetics, has done some work exploring “manosphere” and misogyny, and says that her interactions with young men paint a nuanced picture.

“Young men in particular — at least, the ones that want to come and reach out to me — do have bullshit detectors,” she says. “On the other hand, when you are in that echo chamber, you are kind of stuck with running with the crowd, but, at the same time, you have this cognitive dissonance with your own family relationships.

“They might be pushed into making slurs about women, or going down the trad-wife viewpoint [a movement that celebrates traditional gender roles, in which women focus on home-making and bringing up children] . . . But at the same time you go home and think, ‘I don’t want to treat my mother, sister, friends at school like this.’”

Responsible for all enquiries that come in about new religious movements and spiritualities, she is also the national officer for deliverance ministry, and runs various social-media accounts open to the general public. She has noticed a “massive uptick” in interest in spirituality and the Christian faith, and points to the pandemic as the catalyst for “profound spiritual questions about what the pandemic meant”.

Young people tell her that they have encountered angels and supernatural beings, heard a voice that they think may be God, or woken from “very intense dreaming”. They wonder about what message they are receiving, and whether they should go to a medium or spiritualist. She has also noticed an interest in Carlo Acutis, the British-Italian teenager due to be canonised in September. Many enquiries are prompted by popular culture, such as TV shows, with questions about how Christian moral teaching might apply to scenarios such as the stalking depicted in Baby Reindeer (Features, 9 May)

WHILE young people may demonstrate high levels of interest and openness to spirituality, those working with them advise against assuming that this will map easily on to Christian teaching. While some insist that young people are longing for a “full-fat”, demanding faith, research conducted among those not currently in church paints a more complex picture.

A Scripture Union/Youthscape survey of 1000 12- to 17-year-olds, carried out in 2022, observed of the gospel: “The more specific the story gets, the more divisive, confusing, and interesting it gets. Many young people are OK with the idea of a loving God who created us and doesn’t give up on us when we make mistakes. But, for most, it doesn’t follow that we need saving, that God would become human, or that death and resurrection are necessary for this. And the idea of God wanting a relationship with us, to transform us or be close to us, is off-putting for some young people.”

The young people studied were “not particularly interested in personal or social accountability as being good news”, the researchers reported. “They were more interested in just being loved.” Neither were they “particularly drawn to the idea of a God who suffered and understands vulnerability”. In their comments, love meant “giving people the freedom to be themselves, not judging them, and accepting others no matter who they are”.

Dr Richards suggests that entering into the “mystery” of God may initially be more appealing than doctrine, and that a primary driver may be the yearning for “a place to find peace, to find rest”. Many teenagers and their teachers tell her that they “just find the modern world exhausting . . . dealing with this barrage of information and truth and lies all the time”.

“I certainly think that the Holy Spirit is finding a way into the lives of young people,” she says, “but just not by the sort of routes that we typically expect.” Her advice to churches is to “have some idea of what popular culture looks like. What kind of thing are they watching on Netflix? What videos games do they play? What chat groups are they on? Where are they getting their information about the world? And not to just dismiss that as strange or unhelpful. Create space for them. Modern life is exhausting. Don’t immediately see them as ready for lots and lots of jobs.”

REPORTS of dreams, angels, and voices lend weight to the advice offered to the Church by the historian Tom Holland, to “keep Christianity weird”. This was a perspective shared by Dr Belle Tindall, who works at the Centre for Cultural Witness, during the Church House webinar on revival.

People were likely to arrive at the church with “spiritual baggage”, she suggested, and it would be important not to “demonise or dismiss” what had come before, but to practise instead a “generous curiosity”. Failing to keep the Christian story “big” risked “playing the disenchantment game . . . which is losing ground”.

DUNCAN HEGANOn the National Pilgrimage to Walsingham

DUNCAN HEGANOn the National Pilgrimage to Walsingham

Against this backdrop, Dr McAleer’s sense is that much work must now be done on the discipleship and formation of new believers. “We know how important childhood experiences of religion and church are for putting down those roots that lead you into strong faith in adulthood,” she says. “Coming in as an adult, you need help to put those roots down really quite quickly. . . How do you keep these people who are exploring faith?”

She has warned of a certain “fragility” among young churchgoers who, according to the Quiet Revival polling, are more likely than older Christians to say that their faith has been shaken by the media and culture, or undermined when they thought about certain passages of scripture. A recent Evangelical Alliance report on adult converts spoke of divergent needs. Among participants with lower incomes, “no one struggled with the existence of God. . . However, the concept of being forgiven, combined with personal struggles, lifestyle changes they felt they would need to make, and what others would think of them, were most difficult.” Overall, it concluded, “a significant number” of converts were “making some kind of commitment with only a very limited understanding of the gospel” (News, 6 June).

It is an assessment that resonates with Fr Hegan. “Biblical literacy — you can forget about it,” he says. “Cultural literacy around Christianity is very, very low. . . We can’t assume the basics; we have to teach people.” But, preparing for a new lecture series and monthly catechism class, he is confident that there exists a hunger for Christian teaching and the unique claims that it makes about the universe and our place in it: “We are not dealing with people who are hostile. We are dealing with people who are curious, and, in many cases, we are pushing at an open door.”

In Wales, Dr Black reports that every baptism has led to the baptism of others who first attended to watch. Testimonies shared online by young men who have seen “transformations in their lives” have prompted old friends to get in touch and ask to come to church with them. While the term “revival” may provoke scepticism, such stories suggest that the Church may need to follow Dr Tweedie’s advice and not write it off just yet.