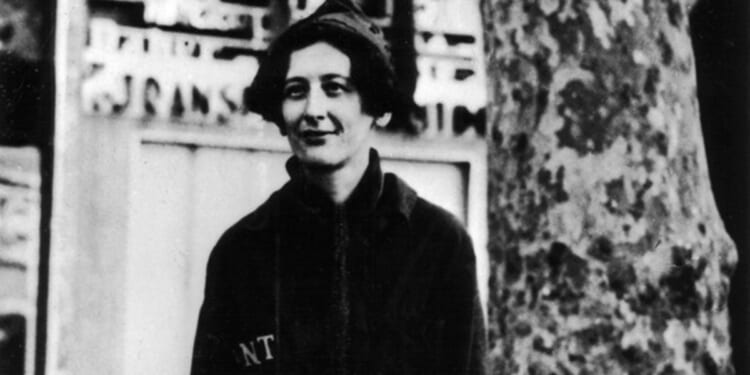

SIMONE WEIL, the French philosopher and mystic, lived almost her whole life in wartime. As a child during the First World War, she gave up her pocket money to sponsor a soldier at the front. She fought in the Spanish Civil War. She spent the Second World War first in occupied France, and then with the Free French in London. She wrote and thought much about war. Now that war is once again raging in Europe, she has something to say to us on the subject.

Like her favourite philosopher, Plato, Weil often expresses her thoughts through analogies. “Suppose we see two men,” she writes: “one is running along erratically, jumping and shouting, while the other is walking quietly and steadily. To which one do we pay attention? Most people will pay attention to the man who is jumping and shouting. But if we know that both men are walking over burning coals, then the one who gains our attention is the person who is walking quietly and steadily. We want to know how he can do this.”

COINCIDENTALLY, the Greek writer Nikos Kazantzakis, in his book The Fratricides, about the Greek Civil War (1946-49), uses the same analogy. The hero of the book, a Greek Orthodox priest, Papa Yannaros, comes from a Greek village where the fire-walking ritual (the anastenaria) is traditional. By faith, he keeps going steadily through fratricidal times in the village where he is a priest, while the other villagers turn to killing each other in a civil war. For both writers, in a world on fire, the Christian is the person who can walk steadily in times of trouble.

George Herbert expresses a similar thought. In his poem “Vertue”, he suggests that only a Christian can resist the fire that is turning the whole world to coal:

Onely a sweet and virtuous soul,

Like a season’d timber, never gives;

But though the whole world turn to coal,

Then chiefly lives.

THE ancient Greek phrase that Weil quotes most often is from Thucydides’s History of the Peloponnesian War. The Athenians have conquered the small island of Melos. If the Melians do not immediately surrender, the Athenians propose to kill the men and make slaves of the women and children. Their emissaries explain: “The strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must.” For Weil, this phrase is the clearest articulation of the ancient belief that “Might is right,” as depicted in the Iliad (on which she is the author of a commentary), whose poet expresses his regret that things should be so.

In the Third Reich, under which she is living, Weil finds the same belief, that “Might is right” — though, rather than regret this state of affairs, the Nazis exult in it. Unlike many of her contemporaries, Weil does not see Nazism as uniquely evil (she dies before the full extent of the Holocaust became known). Rather, she sees it as an extreme manifestation of the world-view that “Might is right.”

In contrast, she believes that, rather than vilify those with whom we disagree by caricaturing them as mad or stupid, we can combat them all the more effectively once we have understood the world from their point of view.

She also recognises that, while living in a country at war may severely restrict the freedom of its inhabitants, occasionally war will open up possibilities of action that would not exist in peacetime. Through her contacts, Weil — a Jew, thrown out of her teaching job by the Vichy regime — is able to get the commander of an internment camp for Vietnamese labourers dismissed by that same regime for gross corruption.

WEIL was a Platonist both before and after her conversion to Christianity. For a Platonist, this world is a shadow of another, more real world. In Plato’s analogy, we are like slaves working on a rock face. All we can see is our shadows cast on the rock face by the sun behind us. The philosopher is the one who can turn from the rock face and begin to look towards the light. Having originally perceived the world as subject to “Might is right” (just as the ancient Greeks did), once Weil converted to Christianity, Plato’s turning to the light meant for her a turning to Christ in prayer.

Prayer for her was always quiet prayer, where she simply waited for God to appear, putting herself to one side. Prayer enabled her to experience another, more real world, where true justice exists.

FOR the Christian, might is not right, nor is it triumphant: evil has already been utterly defeated by Christ in his death and his resurrection. As Bonhoeffer writes in his poem “Who am I?”, composed in prison not long before his death, the evil we see around us is “like a beaten army, fleeing in disorder from a victory already achieved”.

Weil herself walked quietly and steadily through a world on fire — not just with war, but with injustice and oppression. In spite of this, as a professional philosopher, she carried on quietly and steadily writing philosophical articles, right up to the time of her death, in Kent, in 1943. The lesson is not that we should become philosophers: it is that, in a world on fire, we should carry on steadily and quietly doing good, according to the state of life which God has given us.

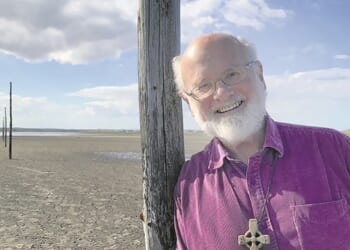

Dr Gervase Vernon is a retired GP.