This past June we published three posts by Chris Flannery on Mark Twain. These posts were the surplus of Chris’s Claremont Review of Books review “Pure gold and his American Mind column “To absquatulate.” The review, the column, and the posts were all triggered by Ron Chernow’s new biography of Mark Twain.

Chris now returns with the American Mind column “The Vindication of Booker T. Washington,” in the course of which Chris links to the late Peter Schramm’s Claremont Review of Books review “The Heroic Effort of Booker T. Washington” on Robert Norrell’s excellent 2011 Washington biography Up From History.

In the concluding paragraphs of his American Mind column on Washington, Chris writes:

Washington never held political office. But his life and work demonstrated that you don’t have to hold political office to be a statesman, and that the noblest work of the statesman is to teach. The soul of what Washington sought to teach was that we too can rise up from slavery. It is an eternal possibility.

This was the central purpose of Booker T. Washington’s life and work: to liberate souls from enslavement to ignorance, prejudice, and degrading passions, the kind of slavery that makes us tyrants to those around us in the world we live in. Washington saw that this freedom of the soul cannot be given to us by others. Good teachers and good parents and friends, through precept and example, can help us see this freedom and understand it, but we have to achieve it for ourselves. When we do, our souls are liberated to rule themselves by reflection and choice, with malice toward none, with charity for all.

If you read Up from Slavery, you will be reading an American classic and will be getting to know a man who, in the quality of his mind and character, and in the significance of what he did in and with his life, ranks among the greatest Americans of all time—even with the man whose name he chose for himself….

Chris’s column reminds me of the productive partnership that Washington formed with Sears magnate Julius Rosenwald dating to 1911. It started with Rosenwald’s donations of shoes and hats for industrial school students in the South.

In 1913 Washington recruited Rosenwald to join the board of the Tuskegee Institute. As Norrell writes in Up From History, “By that time, Rosenwald and his wife were enamored of Tuskegee and persuaded that black education in the South should be a particular concern of theirs.”

Washington sought Rosenwald’s support for the building of primary schools throughout the South. Rosenwald initially offered prefab buildings then being sold by Sears, but Washington had a better plan. Black residents of the benefited communities had to be involved in the construction process. Norrell recounts that Rosenwald agreed to underwrite six schools at a cost of $2,800.

Upon completion Washington sent Rosenwald photographs of the buildings and accounted to Rosenwald for every penny spent. Washington also reported to Rosenwald: “You do not know what joy and encouragement the building of these schoolhouses has brought to the people of both races in the communities where they are being erected.”

The Rosenwald schools project continued in 1914 with Rosenwald’s commitment of $30,000 to build 100 schools in three Alabama counties. Indeed, the project continued “long after Washington had left the scene,” as Norrell puts it.

Norrell leaves the story sith Washington’s exit from the scene. For the rest of the story one must go to the 2015 Aviva Kempner film Rosenwald. I could not believe that I had never heard of the story before we saw the film at the local arthouse theater in Edina. It is a moving and inspirational story. The 16-minute documentary The Untold Legacy of Julius Rosenwald provides the essential elements of the story.

The documentaries mostly tell the story and leave us to draw our own conclusions. Mine was that true philanthropy requires genius every bit as much as business success does. There is in any event much to be learned from the story.

Andrew Feiler picked up the story and documented it in A Better Life for Their Children: Julius Rosenwald, Booker T. Washington, and the 4,978 Schools that Changed America, published by the University of Georgia Press, and in an exhibition of photographs that ran in Atlanta’s National Center for Civil and Human Rights. Feiler too only learned of the story in 2015 and, like me, could not believe he hadn’t heard of it before.

Feiler wrote up a brief account of his journey with accompanying photographs in the 2021 Wall Street Journal Review column “The 4,978 Schools That Changed America.” Feiler writes in his column:

Inside the small white clapboard Cairo School in Sumner County, Tenn., brothers Frank and Charles Brinkley stand under the watchful gaze of a once towering figure in American business. The portrait of Julius Rosenwald, who led Sears, Roebuck & Company for almost three decades at the start of the 20th century, has hung in the schoolhouse since it opened in 1923.

The building, now a community center, is a surviving testament of one of the most dramatic and effective philanthropic initiatives the U.S. has ever seen. From 1912 to 1937, a collaboration between Rosenwald and Booker T. Washington of the Tuskegee Institute built 4,978 schools for Black children across 15 Southern and border states.

Today, at a moment when America seems torn along racial and regional lines, when debates around opportunity, infrastructure and the American Dream ripple across the country, the remarkable success of the Rosenwald-Washington partnership is a reminder that people from divergent experiences can come together to effect real and lasting change.

The Brinkleys bear witness to the multigenerational impact of this program. The brothers attended the one-teacher school in the late 1940s and early 1950s. They went on to college and graduate school, and both became educators. They have four sisters, each of whom also attended the Cairo School and college; the siblings’ 10 children all went to college. Without this schoolhouse, that legacy may not have happened.

Born to Jewish immigrants, Julius Rosenwald led Sears from 1908 until his death in 1932. He helped turn the company into the world’s largest retailer, and he became one of the earliest and greatest philanthropists in American history. Booker T. Washington, born into slavery, became an educator and was the founding principal of the Tuskegee Institute.

Rosenwald and Washington met in 1911. At that time, Black public schools in the South were usually in terrible facilities, with outdated materials and a fraction of the funding provided for educating white children. Many communities did not even have schools for Black students. The two men, forging one of the earliest collaborations between Jews and African–Americans, brought together Black communities and white school boards to create this transformative program.

I first learned about this partnership from a preservationist in early 2015 and was shocked that I had never heard of it. I am a fifth-generation Jewish Georgian and civic activist. The pillars of this story are the pillars of my life. I set out to document it with black-and-white photographs that paid homage to the program’s history.

Of the original 4,978 Rosenwald schools, about 500 survive. Over three and a half years, I drove 25,000 miles across all 15 program states and photographed 105 schools. The photographs include interiors and exteriors, schools restored and yet-to-be restored, and portraits of people with compelling connections to these structures.

The Rosenwald schools program was a watershed moment in the history of philanthropy, and not only because of its mission, scope and impact. It was also an early example of challenge grants, public-private partnership and a benefactor mandating that all funds be expended within a set period after his death.

Perhaps the most enduring legacy of these schools was their graduates, many of whom went on to become foot soldiers in the civil rights movement. Medgar Evers, Maya Angelou and John Lewis attended Rosenwald schools. As the late Rep. Lewis wrote of his experience: “I was curious. I was hungry to learn. I was absolutely committed to giving my all in the classroom. My parents would describe education in almost mythical terms, that it offered the keys to the kingdom of America, the keys to a better life and to opportunity so long denied our race.”

Julius Rosenwald and Booker T. Washington reached across divides of race, religion and region and together created a pathway for a generation of children who might not otherwise have had one. In the process, they changed the country they loved.

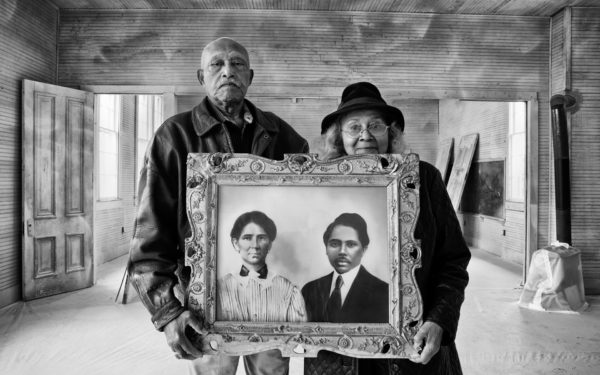

The Journal story includes Feiler’s photograph below with the caption: “Elroy and Sophia Williams hold a portrait of Sophia Williams’s grandparents, former slaves who acquired and donated land for a Rosenwald school.”

At one of our presentations on Rathergate 20 years ago, John and I met Rosenwald’s granddaughter Nina in New York City. Nina Rosenwald is founder and president of the Gatestone Institute and “a lifelong defender of American principles of liberty, freedom of speech and peace through strength. Her work supports the rights of religious minorities, pro-democratic institutions and women around the world.” Nina too embodies the legacy of Julius Rosenwald.