THE Bible Society’s report The Quiet Revival, published earlier this year, said that “Church decline in England and Wales has not only stopped, but the Church is growing” (News, 11 April). Yet this year’s Statistics for Mission show that the Church of England is, by almost every measure, smaller than it was in 2018 (News, 31 October). In 2024, attendance rose for the fourth year, but recovery since the pandemic has slowed.

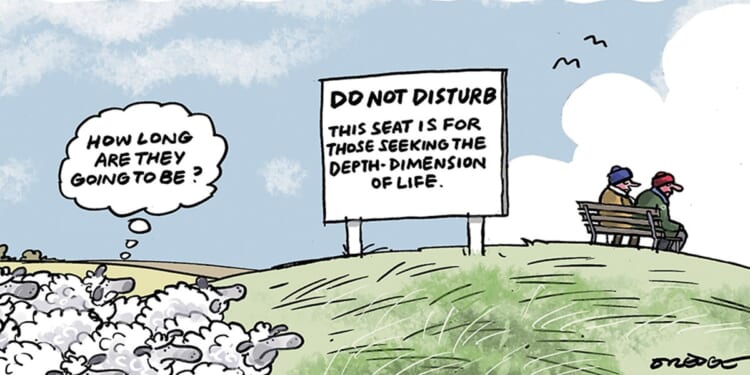

Perhaps the real story is being missed — one that is not about attendance figures, but about a rising tide of people seeking the depth-dimension of life — what often gets called “spirituality”.

The 2021 Census and the 2022 Theos/YouGov study The Nones (News, 2 December 2022) show that, while fewer people now identify as Christian, a growing group who describe themselves as “non-religious” still believe in God, a higher power, or some form of the supernatural. The data point to a significant number who might be described as “spiritually inclined but unaffiliated”. How might the Church respond to this?

There are plenty of offerings from other religious traditions for people drawn to the sacred. And yet, says Martin Laird, one of the leading writers on Christian contemplative practice today: “While we continue to see fewer and fewer people regularly attending church services, their deep, genuine longing for the depth-dimension of Christianity has only grown. . . Sadly, most Christians have absolutely no idea that Christianity has anything to say about this, much less that it has its own vibrant contemplative tradition. This is largely due to the fact that it has never been presented to them.”

I BELIEVE that a quiet revolution is under way. At the School of Contemplative Life, we host twice-weekly online meditation gatherings, following an ancient practice of the early Christian desert contemplatives. No music; a few words; then meditation practice.

These gatherings have quickly become host to the largest online Christian meditation community in the UK. Many who join are not churchgoers. Some would not call themselves religious, and yet they are drawn to silence. They recognise the wisdom and healing to be found in this simple, ancient way of prayer.

In a preliminary study with the University of Derby, 87 per cent of the participants said that, since practising in this group, they felt a deeper connection with God; 83 per cent said that their lives were more aligned with their values; and 76 per cent reported greater inner peace. As one person put it, “Peace now feels tangible, and possible, and present — not just an idealistic goal.”

In an age of distraction, division, and digital noise, people are not turning away from spirituality, but seeking ways to explore and nurture it; and yet, in their efforts to attract people, some churches look to the marketplace — slogans, sleek branding, artisan coffee — rather than what is under their noses.

I was not raised in a religious home, but I was spiritually thirsty. As a teenager, I discovered a book by the Benedictine monk Bede Griffiths, which led me to Prinknash Abbey, where I lived for a while and first encountered Christian meditation.

Here, I discovered that silent prayer has always been part of Christianity — that the contemplative dimension lies at its heart. This essential dimension of Christian life has been neglected for centuries, particularly in the West. The wisdom practices once taught for engagement with, and the interpretation of, life and scripture have been largely forgotten.

When people meditate together in silence, something wonderful happens. Fixed perspectives soften; compassion grows and flows. As one of our practice community said, “I used to cross the road to avoid certain people; now I cross over to see them.”

In an anxious and fractured world, this is a precious thing. As we learn to greet our thoughts and feelings with greater silence, a space of opportunity opens in which to see better those around us: their needs, their mysterious beauty and dignity, and our own.

MEDITATION is a school of community, a school of oneness, a quiet path to being fully awake and gratefully present. I am not suggesting that meditation alone will solve the institutional Churches’ problems or the world’s. But, unless we recover the depth-dimension of Christianity, many churches may remain dislocated from the spiritual wellsprings for which so many thirst.

The future of our churches will not be found in chasing numbers, but it may be found in rediscovering the contemplative wisdom that has been almost forgotten. As Rowan Williams writes: “Contemplation . . . is the key to prayer, liturgy, art and ethics, the key to the essence of a renewed humanity.”

Meditation is an ancient jewel within the riches of a contemplative tradition, which might be described as the missing piece of much contemporary Christianity. As we learn to be still, to be silent, we come home to the boundless love that has held us from all eternity. We come home to each other and to God.

Chris Whittington is the founder of the School of Contemplative Life.

The Missing Peace: Meditation as a spiritual path to peace, community and oneness is published by Canterbury Press at £12.99 (Church Times Bookshop £10.39); 978-1-786-22679-2.

themissingpeace.org.uk @schoolofcontemplativelife