BISHOP LESLIE BROWN in his funeral address for Benjamin Britten said: “He believed deeply in a Reality which works in us and through us and is the source of goodness and beauty, joy and love. He was sometimes troubled because he wasn’t sure that he could give the name of God to that Reality.”

This exhibition, ably curated by the Revd Dr Paul Edmondson, is based on the understanding that, although not a regular churchgoer after his childhood, Britten nevertheless created much sacred music connecting personally with the themes, people, and churches involved, while his approach to God and the music that he composed was shaped initially by the Christian values and routines of his childhood.

Among the specific works featured in this exhibition are Rejoice in the Lamb, commissioned in 1943 by Walter Hussey for the 50th anniversary of the opening of St Matthew’s, Northampton, and the War Requiem, commissioned for the consecration in 1962 of the new Coventry Cathedral. The latter showcased his pacifist views, through his weaving together the Latin words of the requiem mass with the anti-war poetry of Wilfred Owen. A later work, his pacifist opera Owen Wingrave, contains a peace aria in which these words are found:

In peace I have found my image,

I have found myself

. . . Peace is not silent

It is the voice of love.

In a statement made in 1942 to the local tribunal for the registration of conscientious objectors, Britten explained how central such beliefs were to his life and practice: “The whole of my life has been devoted to acts of creation (being by profession a composer) and I cannot take part in acts of destruction.”

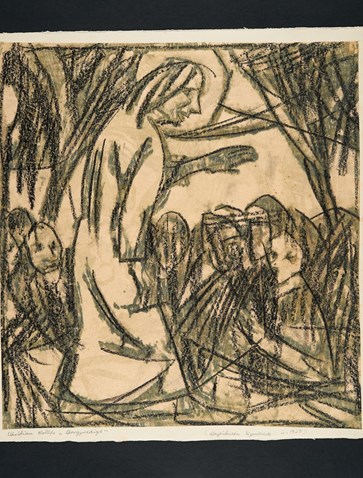

BPAChristian Rohlfs, Bergpredigt (1925), charcoal, woodcut

BPAChristian Rohlfs, Bergpredigt (1925), charcoal, woodcut

Joanna Bullivant has noted that “Britten’s pacifism and left-wing politics . . . formed — with his sexuality — a nexus of othered identity” that was, as his partner, Peter Pears, had it, “‘outside the pale’ in British society of the mid-twentieth century”. “Britten’s left-wing pacifism” also, however, “intersected with broader trends and attitudes, and other radical individuals”, including clergy, such as Dick Sheppard, who were involved in the Pacifist movement.

The exhibition explores Britten’s spirituality through six strands: spiritual music as a lifelong vocation; the security that he felt in childhood; the wonders of creation; love and desire as expressed in his music; his rootedness in Suffolk as his home; and his openness to other musical traditions.

Pears and Britten built up an outstanding and highly personal art collection, which also expressed their interest in spirituality through their patronage of artists who expressly explored religious themes and images. These include William Blake, Geoffrey Clarke, Cecil Collins, Georg Ehrlich, Eric Gill, Samuel Palmer, John Piper, Christian Rohlfs, Georges Rouault, and Francis Newton Souza. Some of these became personal friends of the pair.

“Darkness” is an exhibition of monochromatic works from their collection, which includes work by Roderick Barrett, Max Beckmann, John Craxton, Duncan Grant, David Hockney, Sidney Nolan, Palmer and Piper while providing an opportunity to journey from exquisite Japanese animal figuratives to Diana Cumming’s curious gem of a sketch, Miss Greek, in which the subject stares baldly at the viewer.

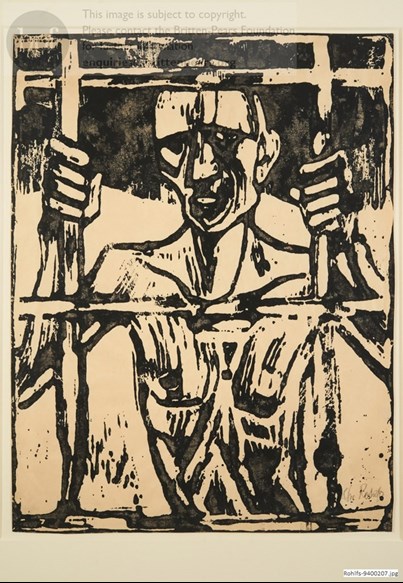

Another meaning of darkness also emerges in this exhibition: the heavy, sad, and even vilified subjects of some of the artworks that Pears and Britten were not afraid to acquire. Collins’s The Agony in the Garden, Souza’s The Agony of Christ, Josef Scharl’s Dead Prisoner etching, and Christian Rohlfs’s Der Gefangene all remind us of the more sombre and painful facets of life. They may also have connected these two brilliant men with the more painful, but also spiritual, facets of their own lives.

BPAChristian Rohlfs, Der Gefangene (1918), woodcut

BPAChristian Rohlfs, Der Gefangene (1918), woodcut

In Bergpredigt, Rohlfs gives us an animated and compassionate Christ, who, in the white space between trees, stretches out a hand of blessing as he teaches the darkened crowd huddled together at his feet on the mountainside. Collins wrote of Christ as the “divine fool, whose immortal compassion and holy folly placed a light in the dark hands of the world”.

The chalice in his The Agony in the Garden is, as Richard Harries has pointed out, “not just the cup of suffering of traditional iconography”; for its unusual shape is also to be found in “an early picture of the artist and his wife where it clearly stands for the cup of inspiration and love running over”. That shape is then “reiterated in the shape of the bodies of Christ and his disciples”. Mark Oakley has noted the “raw energy” of Souza’s crucifixion paintings, which, as with The Agony of Christ, bring us back “to the horror of Christ’s public execution” and invite us “to interrogate the pains and cost of love and how this love might, indeed, reflect the divine”.

Such images convey something of the Reality in which Britten found, according to Bishop Brown, the source of goodness, beauty, joy, and love.

“Spiritual Britten” runs until 1 November 2026 and “Darkness” until 2 November 2025 at The Red House, Golf Lane, Aldeburgh, Suffolk. Phone 01728 451700. Booking: 01728 687110. www.brittenpearsarts.org