The Roberts Court has attracted headlines overturning longstanding and high-profile precedents, including Roe v. Wade and Chevron v. NRDC. This term, the Court appears poised to topple another, Humphrey’s Executor, if (as expected) it upholds President Trump’s removal of Rebecca Slaughter from the Federal Trade Commission.

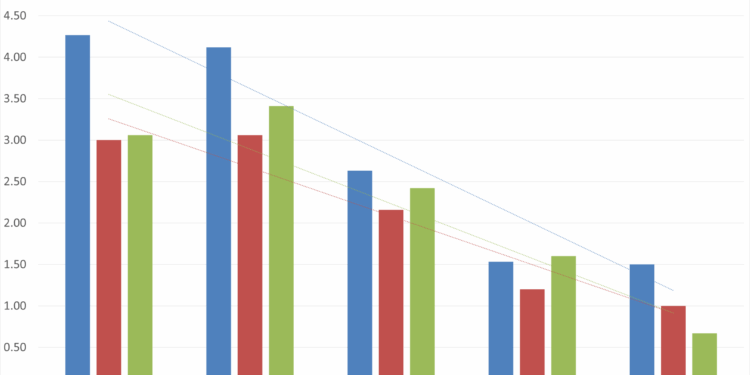

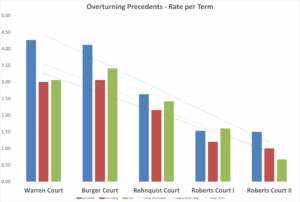

In the past, I have noted that the Roberts Court has overturned precedent less often than did the Warren, Burger, or Rehnquist Courts. Indeed, as I’ve blogged repeatedly and written in National Review, it is not particularly close, as shown in data compiled by the Library of Congress and in the Supreme Court database (which includes precedent alteration in its tabulations).

Given the rash of recent decisions overturning prominent precedents, it is reasonable to ask whether this claims are still true. The answer? Thus far it is. Even though the Court now has a six-justice conservative majority, which should make it easier to overturn precedents at odds with conservative jurisprudential principles, the rate at which the Court is overturning prior precedents has not (yet) increased. To the contrary, it appears to have slowed.

If one divides the Roberts Court into the first Roberts Court (2005-2020) and the second Roberts Court (2020-present), the rate at which the Court has overturned precedents is actually lower in the second Roberts Court (although for one of the three measures, the difference is minimal).

As illustrated in the accompanying chart, whether one looks at cases overturning precedents per term, precedents overturned per term, or decisions altering precedent per term, we have not yet seen an increase in the rate at which the Roberts Court is overturning prior precedents. The confirmation of Justice Barrett to replace Justice Ginsburg unquestionably made the Court more conservative–and likely led to the overturning of Roe in Dobbs–it did not produce an immediate increase in the rate at which the Court has been moving the law in a conservative direction by overturning prior precedents.

These results may be surprising. There are multiple reasons why the shift from a 5-4 Court to a 6-3 Court would be expected to increase the number of precedents in jeopardy and the rate at which those precedents are overturned. It just has not happened yet.

One reason the Roberts Court has not overturned more precedent is that it hears fewer cases. It is stingy about granting certiorari, so it has fewer opportunities to overturn precedents.

At the same time, the Court appears somewhat deliberate about what cases it takes, and that includes what precedents it wants to revisit. The Court is overturning fewer precedents, but the precedents it is overturning may be higher profile. This may reflect a preference for stability in the law, accept when it comes to particularly significant decisions that push against the majority’s jurisprudential vision.

I suspect it has been easier for the justices to coalesce about the need to overturn precedents that have long been targeted by conservative jurists, and for which the arguments for overturning the precedent are well developed and there is a fairly clear idea for what might replace the precedent. Roe, Chevron, Abood, and Bakke would all fit these criteria. But the number of such cases may not be as long as some think. And if the justices are hearing fewer cases, they are less likely to find themselves confronted with a case that requires reconsidering a precedent they had not already targeted.

It is also noting in this regard that since Justice Barrett has joined the Court, every case overturning a precedent that can be so characterized, moved the law in a more conservative direction. This stands in stark contrast to when Justice Kennedy was on the Court, and the Court would overturn precedents to move the law in both liberal and conservative directions, depending on Justice Kennedy’s particular preferences.

It is also important to stress that it is still early, and what we have seen in the past few years–a Court wiling to overturn a few, high-profile precedents–may change. If the justices are interested in revisiting more areas of law, and reconsidering more precedents, cause attorneys and lower courts will likely give them the opportunity to do so.