WHEN Anne Dellows was six years old, she suffered burns to her feet. That summer, she was treated at Great Ormond Street Hospital, where she and other patients would be taken to the chapel for lessons and prayers. It is a memory that remains vivid, 74 years later. Aged 80, she returned to the chapel this year for the first time.

“I walked through the door to the chapel, and I was just transported back to being six years old,” she says. “It felt like the exact same experience. I walked into this beautiful golden room that hadn’t changed. Seeing it again filled me with emotions.”

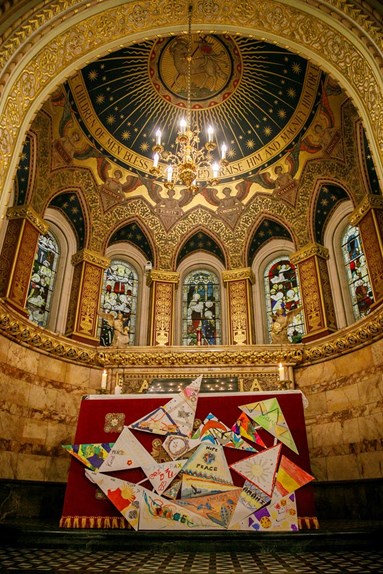

Those who have seen St Christopher’s Chapel, built 150 years ago this year, may not be surprised by its power over memory. Designed by Edward Middleton Barry — whose father, Sir Charles Barry, was principal architect for the Houses of Parliament — its style has been summarised as “Venetian/Byzantine Gothic”, inspired by St Mark’s Basilica, Venice.

Its interior is highly decorated. Huge red marble columns are adorned by flora, fauna, and mythical beasts, while the central dome is occupied by musician angels, hovering over a mosaic floor. There are murals on the walls — including one that depicts “Suffer little children to come unto me” — and stained-glass windows depicting Christ’s childhood. Gold is everywhere. Oscar Wilde described it as “the most delightful private chapel in London”.

GREAT ORMOND STREET HOSPITALThe new altar frontal

GREAT ORMOND STREET HOSPITALThe new altar frontal

THE lead chaplain at Great Ormond Street, the Revd Dorothy Moore Brooks, says that her first impression of the chapel was “that the Victorians got this really right”. She describes it as “a Victorian sensory room. There is so much to see, to touch, to engage with.”

Having seen photographs, she expected it to be “massive, because of its opulence and grandeur”, she says. “And, of course, it almost looks like it’s been shrunk in the wash. It has an intimacy, I think. I feel cocooned in it, and families often use that kind of language. That it’s a place where they feel safe, they feel held. . . Once you’re in, away from the clinical beeps, buzzers, business of a hospital, it just takes you somewhere else, and that’s what people need, I think: to be transported, even for just a few minutes, away from what they are experiencing and to somewhere of beauty and grandeur, and which seems a little bit timeless.”

The chapel is all that remains of the original Hospital for Sick Children, which was given a purpose-built building in 1875, 23 years after it had first opened, with Charles Dickens among its early champions. It was endowed by a cousin of Barry, William Henry Barry, a wealthy city broker, in memory of his wife, Caroline Pitman. A guide by Nick Baldwin, archivist at the hospital, notes that, at £60,000, it cost as much as the rest of the building in total — “a reflection of Victorian priorities”.

From the beginning, the chapel was designed with children in mind. In addition to the murals and stained-glass windows, the pews are child-size. Ms Moore Brooks recalls giving a health warning to Archbishop Desmond Tutu during a visit some years ago, and being told “A perfect size for me then, my dear!”

“There is lots of history, even in the pews,” she says. “You can see the scratches, the fingernails, maybe the little bits of colouring-in. It is a place that children have inhabited, and I love that about it. I see children who are quite restless settle when they come in, because of the light, the warmth of the colours, its yellows and oranges and golds.”

THE chapel is open 24 hours a day, and Ms Moore Brooks reports that chaplains called in to see a family at 3 a.m. will often find a parent present in the pews. “It is a place of refuge,” she says. “Perhaps their child has just gone to theatre for major surgery, and they don’t know what to do with themselves, or where to go.” The prayer tree, commissioned ten years ago, is also a popular feature.

Besides holding daily prayer, a weekly Roman Catholic mass, and services celebrating the Church’s major festivals, the chapel is used to mark events “of great joy and great sorrow”. Maxwell, now one, was baptised there in April, two days after he rang the bell at hospital to signify the end of his cancer treatment. He was born with a cancerous tumour on his liver.

His mother, Claire, was drawn to the chapel during this time. “You look for light and comfort in dark times,” she says. “I couldn’t take my baby home like planned, and my mum, who passed in 2021, was religious and would pray. So, I visited the chapel. It is a place of peace and calmness. It felt as though you were leaving the hospital, and became somewhere that my family and I would regularly visit.”

Being able to take her son to the chapel was “a big goal”, she recalls. “The little milestone of getting him off the drip long enough for him to go was such a great thing.”

The chapel is also chosen by some parents for the funeral of their child — in some cases, having never been able to take them home. A book of remembrance is kept. “Almost every day, a bereaved family arrives to see their precious child’s name in that book of remembrance, and it matters that we keep that, and that we are interruptible in the business of a day to slow things down and spend time with them,” Ms Moore Brooks says.

THE majority of parents and families supported by the multifaith chaplaincy at Great Ormond Street do not regularly attend a place of worship. “Most weeks of my chaplaincy, someone says ‘I don’t know why I am here. I don’t know what I believe, but I felt drawn to come here,’” she says. Sometimes, people ask whether they are “allowed” to have a prayer. “I wonder what our responsibility as the Church is other than to say ‘Yes, you are welcome.’”

JEN KIMBER KREATIVE PHOTOGRAPHYClaire, with Maxwell, at his baptism this year

JEN KIMBER KREATIVE PHOTOGRAPHYClaire, with Maxwell, at his baptism this year

Inevitably, having a child in need of the specialist care at the hospital will often raise “huge questions of why, about justice, about suffering, about the nature of God”, she says. “Often, we find people worry that it’s something that they’ve got wrong in life which has meant that their child is sick, and perhaps one of the roles of a chaplain is to reframe that image of God gently, kindly, compassionately, and speak about . . . the loving nature of God who weeps with us. Sometimes, we experience people who are pretty angry, and why wouldn’t they be? It’s outrageous that a child should be born with a brain tumour, for example.

“And, sometimes, our role is to help people safely to give voice to those huge feelings and that legitimate anger. I find the Psalms really helpful in that, in terms of saying it’s OK to bring those questions and that sorrow to God. . . There are times as a chaplaincy team where all we have left is the sorrow and tears of lament, as well.”

She sees faith literacy as a “core part” of the chaplaincy’s purpose: “To interpret those things which matter to the family to colleagues who might hold a different view, or see life, health, death, suffering, through different lenses.”

When the chapel opened, in 1875, there was an assumption that everyone was a Christian, she observes. Today, the hospital is home to a Muslim prayer room, a Jewish shabbat room, and a non-religious reflection room. “Chaplaincy has broadened out, and rightly so, as society has, and that’s part of the richness of what we offer. . . Chaplaincy is for everyone.”

That includes the hospital’s 6000-strong staff, many of whom “book-end” their shifts at the chapel.

THE affection in which the chapel is held has perhaps no greater testimony than the efforts that were made to transport it, wholesale, to the hospital’s new location, in 1990. Underpinned with a concrete base, it was moved on a hydraulic device over three days. Frank Bruno, the boxer, and a group of patients gave it “a symbolic push to get the process under way”, Mr Baldwin recounts. It was reopened with a re-dedication service four years later (News, 6 May 1994).

GREAT ORMOND STREET HOSPITALThe exterior of the chapel, in readiness for the move by means of a hydraulic device in 1990

GREAT ORMOND STREET HOSPITALThe exterior of the chapel, in readiness for the move by means of a hydraulic device in 1990

This year’s anniversary has been marked by projects involving children, including the creation of a new altar frontal that features words in different languages. Now 15 years in her post, Ms Moore Brooks believes that serving the children who take their places on the chapel’s miniature pews has had a profound effect on her own faith.

“I think it’s taken me to a far more authentic place — a place where we don’t have to be good about suffering,” she reflects. “We can name it for what it is. It’s also taken me to a place where I’ve understood more that our faith doesn’t have to be complex: unless we come as a little child, we shall not see the Kingdom. The children each day teach me that in their honesty, their legitimate questions about why this is happening, or why God has not answered the prayer in the way we hoped. . .

”Theology is quite complex when a child is very sick; so I don’t want to minimise those themes, but I think, for me, there is something about holding on to hope, holding on to the light, and holding on to simplicity in faith, a childlikeness. And, in some ways, that is incredibly liberating. I don’t have to have it all sewn up. I can just come to God as I am, in the way that a three-year-old or 11-year-old might, just as we are.”