IN MAY 1904, Queen Margherita of Italy stayed in the Grand Continental Hotel in the heart of Siena with her late husband’s cousin and brother-in-law, Prince Tommaso Duca di Genova. There the commemorative plaque on the principal staircase still celebrates them as ospiti amati, “much loved guests”, as the dowager queen and the new king’s uncle based their courts in the hotel for six days.

They had come for the exhibition of “Arte Antica Senese”, opened by King Vittorio Emanuele III a few weeks earlier on 17 April. It was mounted in forty rooms of the Palazzo Pubblico, and visitors needed to reach rooms 26 to 30 to see the paintings, sculptures, and fabrics of the early 14th century now in the latest exhibition to open at the National Gallery in its bicentennial year.

The 378-page catalogue listed works from the 13th to the 18th centuries. Although not as extensive, the exhibition “Siena: The Rise of painting 1300-1350”, first seen last year at the Metropolitan Museum in New York, is every bit as ambitious, based on more than a century’s scholarship and developing conservation techniques. Its scholarly catalogue, edited by the curator Caroline Campbell, runs out at 312 pages.

Interest in Sienese art from British and American collectors, many less scrupulous than others in exploiting impoverished nobility and ignorant parish clergy, had grown rapidly at the turn at the century. Locally, Italian artists played this to their own advantage, establishing a market for works of art from Siena, hitherto regarded as inferior to those of Florence, and flooding the market with fakes.

The millionairess New York-born bohémienne Isabella Stewart Gardner had already purchased the delightful Simone Martini Virgin and Child with Saints Helen, Dominic, (?) Stephen and a Dominican nun (c.1325) in 1897 for her museum in Boston.

© Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

© Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

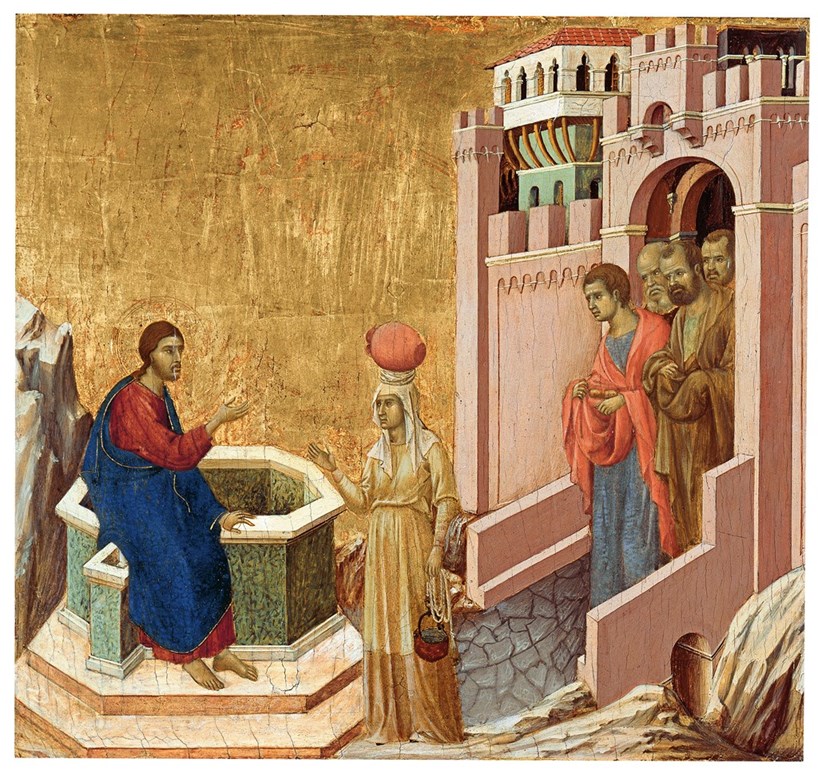

Duccio, Maestà: panel (1308-11), Christ and the Woman of Samaria,

tempera and gold on panel, 43.5 x 46cm, on loan from the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid (133 (1971.7))

It had most probably come from the Dominican convent of San Paolo in Orvieto, now a campus for Gordon College, Massachusetts. She obtained the devotional picture from the Florentine artist-turned-dealer Stefano Bardini (1836-1922), who bequeathed his own eclectic collection to the city of Florence. Sadly, it has not travelled to London, but was included earlier in New York (fig.71).

The 1904 exhibition was curated by Corrado Ricci (1858-1934), who was successively director of the galleries of Parma, Modena, and, from 1898, the Brera in Milan. He was informed in part by the American art scholars and “fixers” Bernard Berenson and his wife, Mary. In the same year, 4500 visitors in London saw a smaller exhibition of Sienese art at the Burlington Fine Arts Club, organised by Berenson’s rival in a turf war with another art historian, Robert L. Douglas.

Coming soon after the assassination of King Umberto I (1901) and hard on the heels of the many strikes by sharecroppers around Siena which began in 1902 as the mezzadria traditional relationship of landlord and tenant broke down, the 1904 royal visits may have been intended as acts of soft diplomacy.

A united Italy had been a state for more than 40 years. Even if the Tuscan landscapes known to the Lorenzetti brothers and to Duccio were bound to change, the earlier development of medieval art offered lessons for the nation’s future.

The exhibition plunges us in medias res, as new-found confidence transformed art forms that predominantly derived from Byzantine icons. We are led into heaven, with sacred image after sacred image, beautifully lit and closely curated; 25 years into the millennium, the show, which opened in Lent, is unashamedly Christian.

In a society in which stores stock hot cross buns all year, while high-street eateries offer Iftar food and meals during Ramadan, it is welcome that our National Gallery acknowledges our Western culture’s roots in the reality of Christian sacred art.

Two of the three portable triptychs that Duccio painted for Niccolò da Prato (c.1250-1318), Cardinal Bishop of Velletri, are shown in two vitrines side by side. Four panels from the Orsini altarpiece painted by Simone Martini for Cardinal Napoleone Orsini (1263 -1342) are brought together for the first time since the 18th century and unfold, concertina-like, to tell the story of the Passion.

© RMN-Grand Palais (musée de Cluny — musée national du Moyen Âge)/Franck RauxItalian, Sienese, Incense Boat with the Annunciation, (c.1350-75), gilded copper, 10.2 × 9 × 21.5cm, from the Musée Cluny, Paris (Cl. 11157)

© RMN-Grand Palais (musée de Cluny — musée national du Moyen Âge)/Franck RauxItalian, Sienese, Incense Boat with the Annunciation, (c.1350-75), gilded copper, 10.2 × 9 × 21.5cm, from the Musée Cluny, Paris (Cl. 11157)

Eight of the nine predella panels from the reverse side of Duccio’s great Maestá in Siena’s cathedral have been reunited. Only the whereabouts of the first, that of the temptation of Christ in the desert, is now unknown.

It is the construction of this Maestá (1308-11) which forms the fulcrum of the exhibition, in the central octagonal hall. Preceding it, the first room introduces us to its creator, Duccio, who died in 1319. The very first icon-like painting that we see is his Madonna and Child of 1290-1300, the “Stoclet Madonna”, in which the Christ-child reaches up, as if to tug his mother’s white veil. Her blue mantle is fringed in gold, but it is no longer the maphorion in which Byzantine artists robed her in imperial blue, shot through with gold.

Duccio depicts her in the same robe, with its gold stars on her shoulder and in the centre of the headdress, in one of the altarpieces that he made for the Dominican Cardinal of Velletri, a Florentine friar (National Gallery London), of The Virgin and Child with Saints Dominic and Aurea. Both attendant saints manifest signs of the new naturalism that Duccio brought, following the trajectory of Cimabue (Arts, 21 March).

Dominic stands at an angle, his hands holding his Gospel book. Aurea, the Syrian-born Abbess of Paris who died of the plague in AD 666, holds up her right hand in abbatial blessing, her outer mantle caught up under her sleeve.

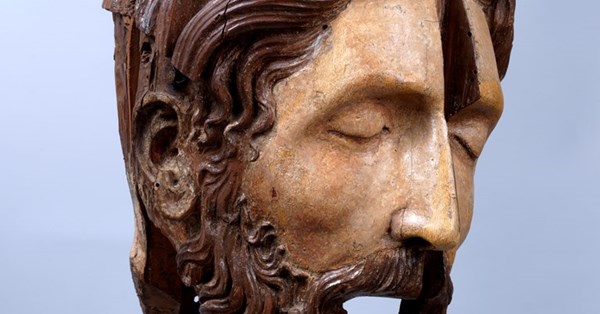

Beyond the octagon, straight ahead, is a room dedicated to Pietro Lorenzetti and the sculptor Tino di Camaiano (c.1280-c.1337), including surprisingly clad caryatids from a wall tomb, while the room on the left has paintings of Simone Martini and images of the Annunciation. The gallery to the right offers a Treasury of items from sacristies, such as reliquary tabernacles, the so-called Galgano crosier, an incense boat with the Annunciation engraved on the lids (Musée Cluny, Paris), textiles from Central Asia and Persia, and delicate ivories with minute carvings.

The final gallery begins with Pietro and Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s work, including the sinopie or chalk under-drawings for an Annunciation from the shrine Tuscan church of St Galgano, and concludes with Simone Martini’s Christ discovered in the Temple (Walker Gallery, Liverpool), poignant and unforgettable, a work dated 1342. Martini wrote his will in June 1344, a few days before he died in Avignon. Many of his peers, most probably including the Lorenzettis, would die in the Black Death, which followed soon after sweeping across Europe from the East in 1347-48.

There is a lot to see; at my first visit, I was absorbed for two hours in the silence of respect, feeling very much like a pilgrim to Siena or to Avignon, where the Papacy was established at the time (1309-76). There is much to meditate on or pray in front of, as one of the gallery custodians told me she often does if she is working and cannot get to mass on a Sunday morning. She will not be alone.

“Siena: The Rise of Painting 1300-1350” is at the National Gallery, Trafalgar Square, London WC2, until 22 June. Phone 020 7747 2885. www.nationalgallery.org.uk