THIS offers the extraordinary story of a duke who had sex with a 17-year-old girl the day after they were first introduced. She was the second daughter of a former king of England, by then the world’s most powerful man, Philip II of Spain. Her elder sister, the Infanta Isabel Clara Eugenia, remained at home, unmarried, until three months before Catalina’s death.

At Zaragoza, in 1585, Princess Catalina married beneath her station. Carlo Emanuele I was merely a duke. Philip was determined to control his empire from Europe and, therefore, needed to ensure ready access to the Spanish Netherlands through the north of what is now Italy. Union with Piedmont and the House of Savoy made most sense.

Between April 1586 and her death in November 1597, the Infanta bore ten children. Carlo was present for all but three of the births.

This was a love marriage, as Dr Sánchez shows from a cache of 3217 letters that the couple exchanged, often daily; 1804 of them (981 in her own hand rather than a secretary’s) are letters that Catalina sent to her husband, who was often abroad on manoeuvres, leaving her, once they had three healthy sons, to govern the duchy when he was fighting to obtain lands from the French to secure his own borders.

Within the strict etiquette of the Spanish Habsburg court, she early learned to correspond with her father, when he, too, was abroad, as King of Portugal. It was a skill that she shared with her sister and that ensured intimate family connections and offered safe diplomatic exchanges. Within that first year of moving from Spain to the edge of the Alps, Catalina’s world changed; with freedom came sleigh rides through the wintry city streets, boating and hunting parties, and shoes not vetoed by her father.

In their letters, they joked about boring courtiers, and designed gardens and plantings. They exchanged gifts of portraits, embroideries, love tokens, fresh flowers, preserves made from fruits in their garden, and fresh produce sent from Nice. Reliquaries and rosaries and captured enemy pennants were all sent with affectionate greetings.

Like all young couples, they had their differences. “I did not marry Piedmont and Turin, but you,” she once wrote, exasperated that she could not join Carlo in Nice “when the snow fell”, as he had romantically promised. But the letters cannot hide the mutual longing for the marriage bed, or the difficulty of maintaining chastity outside it, with only a portrait of the other for company in the night.

When Catalina died, shortly after giving premature birth to their tenth child, her husband was away from home. The Turin Shroud had been brought for her to venerate, and she received communion and the viaticum. Carlo’s grief must have been unbearable.

The three surviving funeral orations preached for her are early examples of the tropes of the Regina fortis (Proverbs 31.10), and of biblical models such as Deborah, as most recently studied by José Javier Azanza López and Silvia Cazalla Canto for Habsburg queen-consorts from the death of Catalina’s mother in 1568 to 1740 (in the journal The Court Historian, August 2025).

Canon Nicholas Cranfield is the Vicar of All Saints’, Blackheath, in south London.

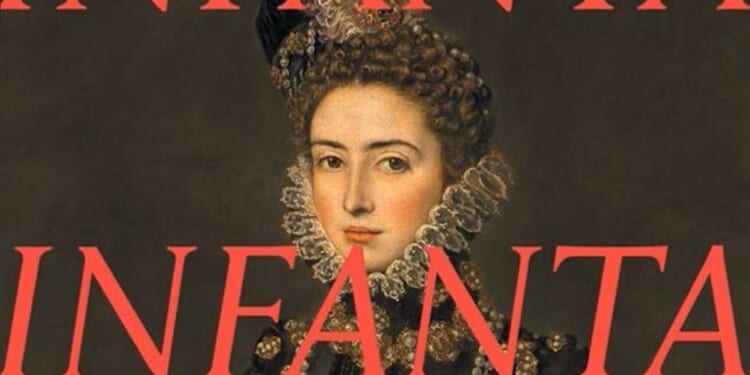

Infanta: The short, remarkable life of Catalina Micaela

Magdalena S. Sánchez

Yale £30

(978-0-300-28283-2)

Church Times Bookshop £27