THE emergence of video conferencing in recent years has had a curious spiritual spin-off: the development of the online retreat.

In Britain, the Carmelites in Oxford were pioneers. Their Prior, and the director of the Centre for Applied Carmelite Spirituality, Fr Alex Ezechukwu OCD, recalls that they moved their fortnightly residential prayer course online in 2018, during a severe winter.

People had been coming in from different parts of the country every other Saturday, but now they no longer had to drive in the terrible weather. Instead, they did the course at home. “That gave us confidence to reposition much of what we were doing online,” he says.

The following year, a young man came for an individually guided retreat all the way from the United Arab Emirates. He had a good experience and wanted to make this a regular practice; but, of course, the distance was an issue, Fr Alex says. “He brought to our minds the fact that, just as you have telemedicine and such things, there could be others in similar situations, living far away, who would benefit from the support of a trained guide.”

The centre held its first online retreat in 2019, just before Covid lockdowns in 2020. Fr Alex sees this as positive. “We’ve had people from Australia, Taiwan, Russia, India, having access to what they would not ordinarily have had access to.”

In Glasgow, the Ignatian Spirituality Centre had had experience of offering spiritual accompaniment online before the pandemic (mostly through Skype), its director, Dr Catriona Fletcher, recalls. “That was partly due to Scottish geography. People in Orkney find it really useful — and people in other parts of the world, too.”

The centre began running online retreats during lockdown, including — in response to demand — the full 30-day Spiritual Exercises of St Ignatius. “I never thought that it would work online, without the support of being together, because it’s so intense, but it did. There was immense movement and grace.”

The London Jesuit Centre for Adult Christian Education, in Mayfair, began regular online retreats in September 2020. Clare Bick has been co-ordinating them for the past four years.

The beauty of a residential retreat, she says, is “the discipline of the silence and the [rhythm] of the place, as well as the lovely countryside and places to pray outside. You have got none of that in an online retreat.

“We call it ‘a retreat in daily life’: whatever you’re doing, whether you’re working, or caring for children or someone elderly, or whatever it is, it’s in the midst of that: it’s not taking you out of that. So, the elements of a retreat are pared down to the personal prayer of the retreatant, ‘accompanied’ by a trained retreat guide.”

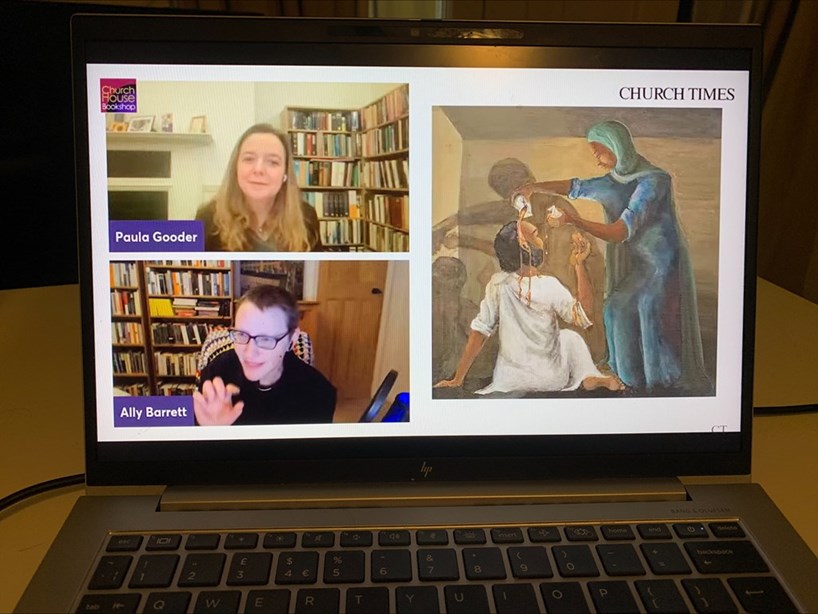

A past online Church Times retreat, featuring Dr Paula Gooder and the Revd Ally Barrett

A past online Church Times retreat, featuring Dr Paula Gooder and the Revd Ally Barrett

St Beuno’s, the Jesuit Spirituality Centre near St Asaph, also began offering online retreats during lockdown. Deirdre Rowe is the team member who co-ordinates them. “The first was a three-day Easter retreat,” she says. “We wanted to give people a chance to be in St Beuno’s without actually being in St Beuno’s.”

The team was not expecting the demand to continue once the house reopened. “But we’re now five years on, and we have run an online retreat every month. There is a steady stream of people who want to do them. A growing number of people come to us from around the globe: from Germany, Singapore, the States.”

Ms Rowe estimates that about half of their online retreatants will have been to St Beuno’s “many times” in the past, but says that the great majority are no longer able to do so. “We have a lovely group now who make an annual retreat online because they’re in care homes, or sheltered accommodation. They couldn’t possibly travel to St Beuno’s, but they can make an eight-day retreat in their own bedroom.”

On one retreat, they had a young couple with a baby, she says. Online, they could “pray around when the baby sleeps”.

Working online opens up possibilities, Dr Fletcher says. “As a spiritual guide, I had someone who was home-schooling an autistic child, who could only meet me at 10 [p.m.]”

“We get quite a few Anglican clergy,” Mrs Bick says. “They might do an online retreat because it’s a busy time of year, and they can’t get away.”

The Scargill Community, in North Yorkshire, started holding quiet days online during Covid, before the present chaplain, the Revd Mike Leigh, joined them.

“I really like the format,” he says. “I don’t think it’s second best. As a community, we talk a lot about whether to keep doing things online, and I always argue that this is really valuable. It’s a different sort of connecting, a different sort of ‘thin place’. I think we can create that experience of getting away from the everyday, even at home.”

Two of their most enthusiastic quiet-day participants are John and Janet Girtchen, a retired Anglican priest and his wife, a former teacher in her fifties. “We had been to Scargill prior to Covid and then everything stopped,” she explains. “We decided to engage with these online quiet days, and we’ve been doing them ever since.

“They allow us to engage with a variety of people that we wouldn’t otherwise meet.”

“They also give us an opportunity for some personal spiritual discipline,” Mr Girtchen adds. “You’ve got to have a bit of self-control, so you don’t just use the day to catch up with all your domestic stuff.”

They still go to in-person retreats, at a diocesan retreat centre near by, “but sometimes their quiet days aren’t very quiet,” Mrs Girtchen says.

Online, with Scargill, “we’re connecting with the community, we’re doing everything that we would normally do if we were there in person; but, when we come offline, we can be as quiet and prayerful as we want to be. That’s something that we really appreciate.”

Oasis Days were originally ecumenical one-day retreats, held once a month in various London churches. In 2020, they went online. Jane Franklin, a member of the organising team, recalls that, thereafter, “because anyone can join from anywhere, the number of people that we connect with grew substantially”.

She believes that online quiet days “have their own strengths. For instance, this month we were looking at pilgrimage, and the couple leading the day invited us to do a mini-pilgrimage in our own garden — or, if you couldn’t get out, to look out of the window and do a sort of pilgrimage in your mind.”

Their sessions are recorded, and so, if someone has missed the day, they can access the recording and have their own quiet time when they can. “That’s a bonus,” Mrs Franklin says.

Another advantage is that “people are online the whole time, and everybody can see everybody else. We have a break in the middle for what we call ‘fellowship lunch’, and, because of the way Zoom works, you hear everybody’s conversations and so you get to know them.

“If you were in a church, and there was a group over here, and a group over there, you might not get to know people. So, there’s a real fellowship that builds up — and if someone has a prayer need, we can instantly hold them in prayer.”

The Church Times, in association with Canterbury Press, began offering half-day retreats for Advent and Lent online during the pandemic. These have continued, and now draw up to 700 people. The three-hour programme of worship and addresses is recorded so that participants can access the content afterwards, as often as they wish to.

“It’s rich fare, and a lot to take in at one sitting,” the publisher at Church House Publishing, the Revd Christine Smith, who hosts these retreats, says, “but, from the comments posted in the chat bar, we know that the model works for many.”

IS IT really possible to create sacred space online? The medium makes no difference, Fr Alex says. “In our tradition, which is a mystical, contemplative tradition, we speak of ‘the mystical space of Carmel’, which is not so much a physical location as a spiritual location. It’s all about the quality of presence, that I am here completely and totally for you. The connection can quite be deep.

“A sacred and empowering environment, a place of beauty, can very easily be created on online. A lot depends on the quality of our presence with the one who is there with us, and how we facilitate that, whether we use art and music and silence to create an ambience where, when they enter the virtual space, they can feel a welcoming presence, knowing what is going to happen there.”

“For me,” Mr Leigh says, “it’s about how we allow God into our lives. People come to Scargill to be able to breathe, to find a spacious place, to open themselves up to God. I think quiet days [online] can do that.

“So often we’re distracted, thinking about what’s coming up, or our regrets for the past. We are very rarely attentive to the present moment. A quiet day is an opportunity to stop and be still, to recognise that God is present. We can create sacred space even in the ordinary and the everyday.”

“Quite a few people go to a beautiful place — a holiday house, or a caravan, or whatever — to do an online retreat,” Dr Fletcher says. “But, for us, that beauty can be a plant in your prayer corner, within your own home or your own room. Or go to a park. Or go somewhere where you get a view over the city, and find God in the noise. God isn’t limited.”

Online “is not for everybody”, Ms Rowe admits, “and, initially, there is sometimes a presumption — on the part of directors as well as people making the retreat — that it will be less good. However, the feedback is amazing. People forget after a while that they’re meeting on a screen, and, in many cases, the direction has been as deep as it would be if the other person was there in the room with them.

“People have made really brilliant retreats on Zoom, and have not felt that [the experience] was sub-standard or second best. God seems to be able to take Zoom in his stride. He doesn’t seem to be constrained by whether he’s got five hours to work with, in a day, or one hour. He seems to meet people where they are.

PixabayPixabay

PixabayPixabay

“Time and time again, I’ve marvelled that a retreat has been so deep and life-changing for people. That it happens on Zoom is nothing short of miraculous.”

Fr Alex concurs. “The depth of transformation that happens in people’s lives through online retreats and courses always amazes me.”

“What surprised me when we first worked online was the depth of connection,” Dr Fletcher says. “I’ve been genuinely surprised at how much movement of the Spirit you can catch so clearly online. I really would not have expected that.”

At the end of each retreat, Mrs Bick says, “we have a time of sharing, which is always very inspiring. A lot of people will have been significantly touched by the retreat, even though it has been without all the normal trappings, if you like.

“People come with faith and expectation, and they are not disappointed. Sometimes, you get people who find that it wasn’t such a good experience for them, but often they come back and have another go.”

beunos.com/retreats/find?hosted=Online

oasisdays.org.uk

scargillmovement.org/online

Online retreats

The next available places for an online individually guided retreat (IGR) run by the Ignatian Spirituality Centre in Glasgow are on 30 June-7 July; 1-8 August; 15-22 August. Cost: optional donation. www.iscglasgow.co.uk/summer-igr

The London Jesuit Centre’s next retreat accessible online, from 6 to 11 July, is titled “Retreat in Daily Life for Summer”. Clare Bick is the tutor. Suggested donation: £125/£62.50. https://londonjesuitcentre.churchsuite.com/events/huc7ceqm

The Church Times’s next online retreat, “O Come Emmanuel”, is on Saturday 23 November, and is based on the Advent Antiphons. Details will be posted on the Church Times website under “Events”.