THE journey that gave us our word deacon was not a particularly long one: from diakonos in Greek, meaning “servant”, it got to us through diacon in Old English. Priest is also from the Greek of the New Testament. Contrary to popular notions, it did not start out as the word for a pagan religious functionary, stretched and misappropriated for Christian ministers, but comes from the biblical presbyteros, meaning an elder.

Perhaps, in the Early Church, a presbyteros and an episkopos were much the same thing. Once the Church took off, and started to grow in far-flung rural areas, however, it became useful for the successors of the apostles to appoint representatives with real but more circumscribed authority in word and sacrament. In that way, words around episkopos attached themselves to the senior, apostolic leaders in the city, while the language of the presbyteros became associated with their junior colleagues. Passing through Germanic forms such as preost, that gave us the English “priest”.

A curate is someone entrusted with the “care” (Latin cura) of a group of people in a certain place (a parish). There are stricter and looser ways of speaking here. More accurately, the curate is the incumbent (entrusted by the bishop with the “cure of souls”), but today we tend to use the word for a clerical apprentice (strictly, an assistant curate), or a non-stipendiary priest (an honorary assistant curate).

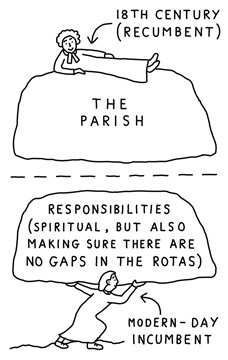

THE word incumbent is useful because it allows us to talk about a priest with the cure of souls without needing to distinguish between a rector (originally, one who rules), a vicar (at first, a stand-in or deputy), or a priest-in-charge.

The etymology of “incumbent” offers some impish opportunities, arising as it does from “to lie or rest upon” (consider the parallel in “recumbent”). An 18th-century cleric, living it up on the financial proceeds of his clerical appointment, certainly reclined on his parish. Happily, the clerical word “incumbent” seems to chart the opposite tack: an incumbent is the person on whom spiritual responsibilities rest.

The sense of a priest leaning on the parish is better preserved in the idea of a parish as a “living”: a job — historically, sometimes simply an appointment and the income, independent of actually doing the job — which provided a sufficient income to live on.

Parson comes from “person”, although quite how or why is not entirely clear. It might be the person who represents the church, or who is entrusted with legal authority.

ENGLISH words to do with bishops split into two groups, in rather a fascinating way. Although “bishop” does not look very much like “episcopacy”, they both derive from the Greek epískopos, which is formed from two parts, epi- (“over”), and skopos (“seeing”, like periscope and telescope), i.e. an overseer. One family of words, including “episcopacy” and “episcopal”, comes through French (where the word for a bishop today is évéque). This family keeps the initial letter “e” in place. Words of a German lineage, however, like “bishop” (and the modern German Bischof), have dropped it. The story is something like this: epískopos eventually becomes biscop (since p to b is a common shift), and on to bishop.

Mitre, by the way, comes from the Greek mitra: a turban or headband). Bishops have been called “primates” (someone of the first rank) since the high Middle Ages. We have used the same word to designate the first rank of mammals only since the mid-18th century.

SENIOR bishops have been described in fatherly terms (Greek pappas) since the early centuries of the Church. We still speak of the bishops of the oldest and most influential dioceses as patriarchs: Rome and Alexandria, for instance, but then also places like Venice and Lisbon. The Greek pappas has also survived as “Pope”, not only for the leader of the Roman Catholic Church, but also for the Patriarch of Alexandria, whether Coptic or Greek Orthodox.

SENIOR bishops have been described in fatherly terms (Greek pappas) since the early centuries of the Church. We still speak of the bishops of the oldest and most influential dioceses as patriarchs: Rome and Alexandria, for instance, but then also places like Venice and Lisbon. The Greek pappas has also survived as “Pope”, not only for the leader of the Roman Catholic Church, but also for the Patriarch of Alexandria, whether Coptic or Greek Orthodox.

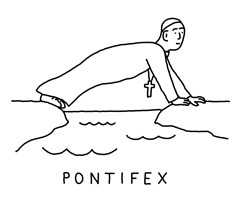

The notion of the pope as Supreme Pontiff comes from the Latin Pontifex, meaning builder (or repairer) of bridges — not, originally, as “helping people get along with each other”, but as erecting a structure for crossing a river. In ancient Rome, that noble task was associated with senior priests. Transfer of that title to the pope reminds us that bishops of Rome, such as Gregory the Great, played a valiant part in practical, economic matters as the Roman Empire collapsed. Today, we say only that the pope is “pontiff”, but the adjective “pontifical” can apply to any bishop in a liturgical context: a “pontifical mass”, for instance, is one celebrated by a bishop.

CATHEDRAL is from the Latin cathedra, meaning chair. The cathedral houses the chair from which the bishop teaches (so literally “the seat of the bishop”). Note the contrast here in late antiquity: the Christian faith is taught openly, in contrast to the gnostic tendency (“gnostic” from the Greek for “knowledge”), by which insights are passed in secret from one initiate to another.

“Ordination” gets that name because it confers a distinctive place in the order of the Church. Since the Church is a body, those who have been ordained have particularly to work for the health and good order of Christian community. To them is entrusted the divine ordering, as Thomas Aquinas put it, by which one Christian delivers the sacraments to another. The idea of a religious “order” is a little different, being a group of people living under a particular rule (Latin ordo).

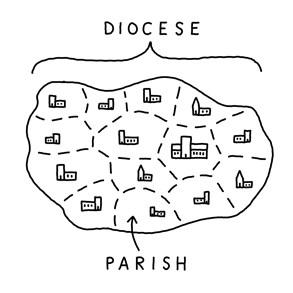

IF OUR minds today tend rather too easily to associate a diocese with matters of economics — with parish share, and diocesan spending — the relation is also there in the etymology. “Diocese” comes from the Greek oikia (household), related to oikos (house, dwelling, family), from which we also get “economics”.

The diocese is the fundamental unit of the household of the Church, a household gathered around the bishop. The bishop directs and manages the diocese, since oikonomia means administration or management. “Ecumenism” comes from the same root (which is clearer if we spell it “oecumenism”).

Theologians also talk about the “theological economy”, meaning everything to do with God’s action in the world. Thus, Karl Rahner spoke about God as the immanent Trinity, when considered simply and eternally in himself, and as the economic Trinity when we think about God’s activity towards his creatures (although Rahner distinguished between the immanent and the economic only so as to equate them).

Like “diocese”, parish also comes from oikos (house), through the French paroche, although the deeper etymology is not so clear. Before the current distinction of the parish as the smaller unit, and diocese as the larger one, the words were sometimes used interchangeably. “Parochial” is simply the adjective relating to parish as a noun. Only in the middle-19th century does it comes to mean narrow or confined.

The Revd Dr Andrew Davison is Regius Professor of Divinity in the University of Oxford and a Canon Residentiary of Christ Church.

Word/s of the month:

”Doctrine” is the body of what the Church teaches (from the Latin docere, to teach, such that a “doctorate” was originally a qualification to teach). When the emphasis is on this teaching as authoritative, we call this “dogma” or “dogmatics” (from the Greek dokeo, to seem or to decide, in the sense that the Church has decreed that which seems right). We call this “systematic theology” when the emphasis is on how the elements of the faith hold together and inform each other.