President Donald Trump has pledged that his tariffs will bring manufacturing jobs back to America and make America a net exporter again. So far, the exact opposite has happened: Manufacturing jobs have decreased, and the trade in goods deficit has increased.

From January through September, the most recent month for which U.S. Census Bureau trade data are available, the U.S. imported $1 trillion more in goods than it exported. This is a $118 billion jump compared to the goods trade deficit that the U.S. ran from January to September 2024. (Likewise, the overall trade deficit, which includes services, increased by $113 billion.)

Perhaps, one might argue, shooting ourselves in the foot (by Trump’s lights) is worth it if it causes our greatest geopolitical adversary—China—to amputate a limb. But that isn’t what happened either.

Recently published data from China’s General Administration of Customs show the Chinese goods trade surplus has increased since Trump took office. From January to September, China exported $875 billion more goods than it imported—a $185 billion jump vs. the same time period in 2024.

Chinese data must be taken with a grain of salt; they’re provided by one of the most repressive governments on Earth. That said, there’s reason to believe these statistics reflect reality. As The Economist explains, China’s $1 trillion trade in goods surplus from January through November is accounted for by “its enterprising manufacturers [expanding] into alternative markets and [discovering] roundabout routes past America’s trade barriers.” (This surplus also excludes trade in services, for which China imports $180 billion more than it exports.)

Supporters of Trump’s protectionist policies might argue that these are growing pains that must be accepted as the U.S. reshores manufacturing jobs and rebuilds the American industrial base. Who cares about the small businesses harmed by tariffs or consumers shouldering higher prices, they might say, if the trade barriers increase blue collar manufacturing employment by a single job?

But even under this rationale, Trump’s policies fall short.

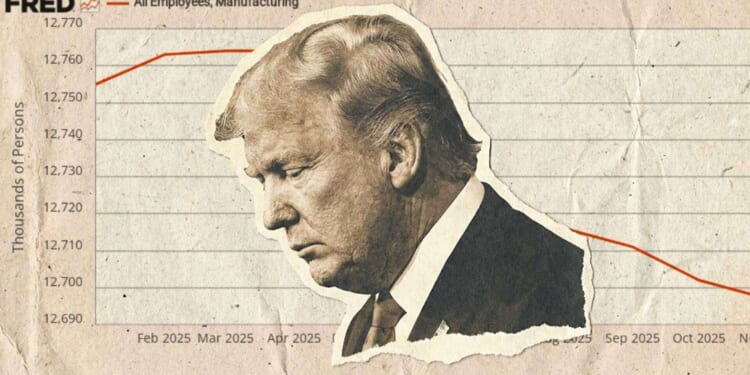

Since Trump assumed office, manufacturing employment has decreased by 58,000 jobs, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ November Employment Situation. Over the same period last year, the manufacturing sector lost 96,000 jobs; so the best Trump can tendentiously tout is a slower rate of manufacturing job loss. (As a share of total nonfarm employment, manufacturing employment decreased steadily from around 40 percent in 1943 to about 8 percent in 2010. It has hovered around there ever since.)

Fortunately for consumers, these macroeconomic statistics are meaningless. You run a trade deficit with your grocery store, I run a trade deficit with McDonald’s, good little boys and girls run a trade deficit with Santa Claus, and we’re all better off for it. As as the economists Daniel Klein and Donald Boudreaux have put it, a trade deficit is equivalent to running a surplus on current stuff.

Likewise, as countries get richer, their labor markets transition from agriculture to industry and then to the service sector. Declining manufacturing employment as a share of overall employment is a sign that Americans are richer, not poorer, than our ancestors.

Trump’s targeted metrics are meaningless as proxies of prosperity. But the fact that his protectionist policies are failing to achieve their stated goals shows just how flawed they—and their justifications—always were.