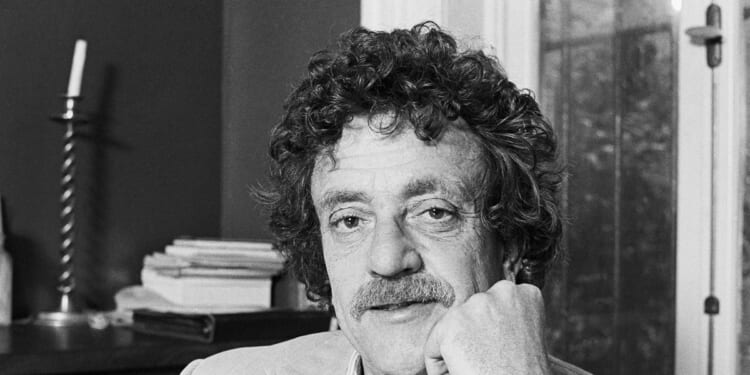

IN KURT VONNEGUT’s novel God Bless You, Mr Rosewater, he has a science-fiction writer, Kilgore Trout, imagine a future in which want and disease have been largely abolished, along with work. You need three Ph.D.s to find a job that isn’t better done by a machine.

To deal with this crisis, the government sets up “purple-roofed ethical suicide parlours” at every major intersection, where pretty hostesses offer their customers a choice of 14 painless ways to die.

“One of the characters [in Trout’s novel] asked a death stewardess if he would go to Heaven, and she told him that of course he would.

“He asked if he would see God, and she said, ‘Certainly, honey.’

“And he said, ‘I sure hope so. I want to ask Him something I never was able to find out down here.’

“‘What’s that?’ she said, strapping him in. ‘What in hell are people for?’”

I hadn’t read the novel in years, but last week came across it in conditions perfect to appreciate the question: under a kind of lockdown in Jeddah, alone in a flat with two cats that I was minding. The heat and smog and the homicidal traffic mean that only the poor and desperate walk anywhere by day; at night, you discover that there are no pavements to walk on anyway, and the cars still prowl in numbers, seeking out whom they can devour. People are here to serve cars, to shop, or to serve shoppers. Only the lack of alcohol and pork hints at some other explanation.

Vonnegut’s answer, which makes the book so haunting now, is that people are here to be kind. Kindness is what he calls the quality, but that’s too milquetoast. In practice, it is closer to love or Christian charity, and the plot of the book is an examination of the price that anyone who tries to practise it must pay.

The hero of the book, Eliot Rosewater, is a rich, handsome, and attractive war hero, who comes from a line of successful capitalist predators: his father is a senator given to sermonising about the evils of socialism; but, on his return from the war, he devotes himself to loving the unlovable: the fat, frightened, ugly, stupid, and self-pitying — all those who, in Trout’s world, would end up at the suicide parlours.

God Bless You, Mr Rosewater is, in fact, the most self-confident work of secular humanism that I know. It is completely secular in that it is not in the least afraid of religion. It takes the absurdity of all religions so completely for granted that it can happily concede their usefulness. Why should not an absurd species need an absurd crutch? This lack of self-importance distinguished Vonnegut from almost every other American humanist in public life.

To understand life as absurd without nihilism is hard. Rosewater manages it only with the help of alcohol, while his wife collapses under the strain of living for others: she suffers from compassion fatigue before the term has been coined. The psychiatrist who treats her writes: “I made it the goal of my treatments to keep her conscience imprisoned but to lift the lid of the oubliette ever so slightly, so that the howls of the prisoner might be very faintly heard. Through trial and error and electric shock, this I achieved.”

Vonnegut explains that the therapist was bound to conclude that “a normal person, functioning well on the upper levels of a prosperous, industrialised society, can hardly bear his conscience at all.”

This is not entirely true, but it is certainly the principle on which a successful newspaper must be edited, on both Right and Left. The triumph of identity politics is, among other things, a demand that all the sacrifices needed to achieve justice be made by other people. Vonnegut is not just concerned with financial inequality, even if the Rosewater millions are the hinge of the plot. Eliot could spread his family money around the unhappy inhabitants of Rosewater county, and, in the end, triumphantly does so by making them all his legal children. Much more difficult are the ineluctable inequalities of talent, health, and temperament.

It is those people whose troubles cannot be cured with money alone. Many are nasty as well as stupid or idle, and it is here that the novel reaches its sharpest point. Rosewater — and, I think, Vonnegut — thinks that they deserve his love anyway because they are human and he can give it. It is, I think, a deeply Christian view that takes for granted that Christianity is absurd, and a humanism that takes for granted original sin.