SCHOOLS and trusts in the UK are showing a growing, if still cautious, interest in flexi-schooling: a hybrid arrangement under which pupils attend school on fixed days — most commonly Tuesday to Thursday — and are home-educated on the remaining two.

Flexi-schooling, a local agreement between the school and families, has been an option since the 1980s, but, in the past few years, there has been a rise in uptake, most particularly in rural areas. Some see it as a means to boost pupil numbers and thus secure the future for small, otherwise unviable rural schools, many of them C of E schools.

The Department for Education (DfE) chose to issue its principal guidance through home-education publications, presuming that the option would typically be favoured by home educators looking for an element of formal schooling in specific subjects.

It did not describe situations in which a child already enrolled in school was granted a flexi-school arrangement, and in which learning was predominantly school-based; nor did it expect that a priority category would prove to be children with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND).

It is more common in the United States, where more than one quarter of a million children with SEND are flexi-schooled or “part-time enrolled”. Far from its being the preserve of wealthy families, as might be supposed, the families have been found, on balance, to be less affluent than those with fully enrolled children, and notably less so than those who are home-schooling.

Earlier concerns about the complexity of flexi-schooling, safeguarding, and the effect on attendance records and test results, were addressed in a review for the Relationships Foundation in 2022. It examined multiple Ofsted reports from schools with significant numbers of flexi-schooled pupils and found that these contained “largely positive statements” on all of these concerns.

School closures during Covid-19 provided evidence of good outcomes that parents had reported. Aberdeenshire Council saw an increase in requests after the pandemic, and reported that, while many parents had found home schooling challenging and had struggled with lack of support, some reported lower levels of anxiety among children who found the school environment overwhelming.

Hollinsclough C of E Academy, Buxton, in the Peak District National Park, proudly proclaims itself “the home of flexi-schooling”. It made the headlines in 2009 when the roll had fallen to five pupils and the school was under threat of closure — something that the community resisted. It was the village hub, the location for community activities and family support. It was even the village office, for photocopying and internet services.

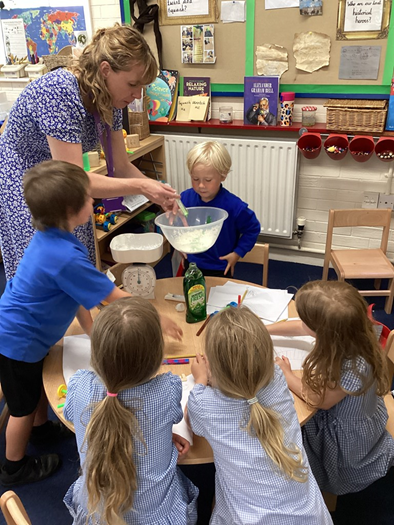

Outdoor learning and explorative play is encouraged with all pupils at Huxley C of E Primary School, Cheshire, to help pupils grow socially and emotionally

Outdoor learning and explorative play is encouraged with all pupils at Huxley C of E Primary School, Cheshire, to help pupils grow socially and emotionally

The former head teacher, Janette Mountford-Lees, received an unexpected enquiry from a parent who home-schooled her children and wondered whether the school might consider part-time education for them. Ms Mountford-Lees is a firm believer that education should be tailored to meet the needs of each child and responsive to their developing abilities. She reckoned that the school could develop a working partnership with parents who home-schooled, and she still sought support from the school system.

The director of education for Staffordshire was supportive, and the local authority set up a pilot project for the year 2010-11. There was a rush of interest and support from home-schooling parents, and the intake of pupils more than quadrupled in three years.

THE school’s new lead teacher, Heather Mottram, who has taken up her post this term, has been at Hollinsclough for more than 13 years. “I came when it was still forming and we were still trying to figure things out,” she remembers.

“When I first began, it was mainly families that had started off doing home education and who began to come here one or two days a week, just to give their children the experience of being in a school, socialising with other children, and learning a subject they couldn’t necessarily do at home.

“Now, it’s very different. We’ve got a couple of children who have come from fully home-schooled backgrounds, but the majority now are those with working parents who have just decided it’ll work a little bit better for them to have those extra hours at home with the children. We have families where both parents work; so they might be working part-time or over weekends.”

The school has 38 pupils, all registered as flexi. Each child has a personalised work plan. They all come into school on Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday each week, when the core subjects of the curriculum — maths, English, history, geography, science, RE, PSHE, and modern foreign languages — are covered.

On Monday and Friday, they have the option to come in for art, computing, and PE, and for any consolidation work they need. Parents fill in a form midweek to confirm whether they will be in school. Project work is done on a Friday, so they can choose either to come in for it, or to use the time at home to pursue their interests or deepen the understanding of what they have learned during the week.

“We can send out things like workbooks, and we’ll also speak to parents about any areas where their children need a little bit of support that would be helpful,” the head says. “But if they choose to go off and visit the Natural History Museum, or go and learn about the London Transport system or something, it’s absolutely fine.

“It works brilliantly. It also means our children spend a lot more time away from a desk. There’s only so much we can teach them from a whiteboard. They can learn so much more by actually going out into the wide world and experiencing those things for themselves.”

Since 2022, Hollinsclough has been part of the Moorlands Primary Federation, a grouping of ten schools, seven of which are Church of England. It’s less of a curiosity now than it was in the early years, when other teachers tended to ask the Hollinsclough staff: “How on earth do you do it all in three days?” And the children mix with a much greater number of others within the federation.

The head describes the children as “gorgeous, every single one of them. They’re friendly and outgoing and caring. You might think that coming from a school that’s smaller and then going to a high school would be a massively daunting thing, but they all seem to just flip straight into it really easily, and engage with each other.”

Contemplating the imminent start of a new school year, she concludes: “I’ve been here for ever. I’m a little bit like a piece of the furniture now, but it’s so lovely to be the one sitting behind the desk and getting to see what else we can do to broaden their experience. I’m incredibly excited.”

HUXLEY C of E Primary School, in Cheshire, adopted the arrangement in 2020, with the arrival of its new head, Rachel Gourley. Like Hollinsclough, numbers on the roll had dropped to just four pupils, and the school was ripe for closure.

The village is tiny: “Just us, and a lot of fields and farms,” Mrs Gourley says. “It’s quite a small catchment, within which is an ageing population that has had children here and stayed living in the houses. That’s why we struggled with the numbers originally, and it’s the same with many rural church schools.”

Children take part in a science class at Huxley C of E Primary School, in Cheshire

Children take part in a science class at Huxley C of E Primary School, in Cheshire

The school had already looked into flexi-schooling as a possibility, and Mrs Gourley says she “jumped” at it. “It was so flexible, and that’s what made me want to come.”

Huxley had a rocky start. Just five months in, it had an Ofsted inspection: “Very cruel, in my eyes, because we were nowhere near ready,” she remembers. “We were graded ‘inadequate’ on governance issues.”

Ofsted has made no further inspections, and the school is now part of the Diocesan Multi Academy Trust (CDAT). An audit under the SIAMS 2023 Framework in July 2024 was positive, testament to the progress made by the children and to the environment that has been created for them.

Quiet zones where the children can go include a reading caravan with blankets, where they can take their shoes off and snuggle down with a book. The school has a spacious outdoor area, including fruit trees, woodland, a wildlife area, and an outdoor classroom, and it also keeps hens.

Inspectors praised it for its “deeply held Christian vision which links directly to the unique context of the school”; its strength as “a highly inclusive and nurturing church school family where everyone is valued for who they are”; and as having “a carefully considered broad and balanced curriculum. This links directly to the vision and aims to meet the needs of all learners.”

It is now more than thriving: it has a record 49 pupils, and is about to open a new classroom, which Mrs Gourley describes as “a huge and beautiful space”.

Pupils come from the Wirral, Runcorn, Nantwich — and even from the border with Wales: one drives an hour and back to the school, twice a day.

A FULL-rotation curriculum runs across the whole year. Parents are not obliged to follow the national curriculum on the Friday or Monday — when the children are at home — but they upload photos, or written work, or diary entries, on a dedicated online platform. All resources for set work can be accessed at home.

“What we find is that they do really rich activities on those days: things like museum visits that complement the topic that we’re doing, or they may be learning an instrument. One of them did fashion design last year, because that’s what she’s really into. It’s giving them that little bit of freedom,” Mrs Gourley says.

Most of Huxley’s pupils are from a SEND background, and others from a home-education background. “When I first started here, it was very much about working on social and emotional support for the children, making them feel safe, secure, and understood,” Mrs Gourley says.

“Some have been in other schools and it simply hasn’t worked out. Just trying to hold it together for five days is too much for them, especially those with autism, for whom the school environment can be stressful.” For these, the school experience is balanced with time at home, where school learning is supported while the child’s need for a less stimulating environment is also met.

“But, in my eyes, it doesn’t have to be all or nothing. Flexi-schooling can be that middle ground between full-time school and home education. It isn’t an approach for everyone, and I totally understand that it is ‘niche’ in that respect, but it is a gap in the market.

“It provides a different, innovative, and brave approach to education that is needed in current times. I think there should be one in every local authority.”

PUPIL numbers are forecast to fall in many areas across the country. There are no predictions about how widely flexi-schooling might be adopted as one route to viability. But the C of E has many small (210 or fewer pupils) and very small (105 or fewer) schools. Of the 108 church schools in the diocese of Norwich, for example, 84 per cent are small, and 51 per cent very small. Fourteen per cent have fewer than 50 pupils.

A strategy document acknowledges: “Small schools are an essential part of our structure, and the DBE is supportive of enabling them to take their place as an educational asset at the centre of their community. However, it is recognised that they can struggle and alternative solutions need to be found.”

Challenges that the diocese acknowledges for small schools include: providing a progressive, sequential curriculum; recruiting staff in rural areas; accessing capital funding for buildings; and recruiting enough governors. Chief among strategies to address falling rolls has been encouraging schools to work in federations, something it has been doing since 2000. Five very small and 21 small schools remain stand-alone.

“We [the Church of England] know how to run small schools,” the diocesan director of education, Paul Dunning, adds. “Teachers are a breed of optimists and problem solvers. Because they’re there for the children, they make it work.”

Department for Education won’t recatergorise flexi-pupils

SCHOOLS have to mark children who are flexi-schooling as on “authorised absence” in the register. This (Code C) absence code is intended for those attending a school part-time, and is used for multiple purposes.

Ofsted noted in its 2023-24 report that, because schools had to record it as such, they could not be sure of flexi-schooling numbers: “At present there is no comprehensive national data about the number of children not in school full time and how they are being educated. The Government has pledged to introduce a register, which we wholeheartedly support.”

A petition launched by Juliette Beveridge, who runs the Facebook group Flexischooling Families UK, called on the Department of Education (DoE) to introduce a new code (Code F) specifically for flexi-schooling. It stated: “We want this code to act in a similar way to Code B (educated off-site) in that it would not negatively impact attendance data, recognising that the child is receiving a full-time education.”

The petition closed in July with 10,869 signatures. The government response, issued on 30 June, said that, having reviewed and updated codes in 2024, it had no current plans to introduce an attendance code for flexi-schooling.

The response states: “When a child is flexi-schooled, it remains the responsibility of the parent to ensure that the child receives a suitable full-time education overall. . .

“Attendance code B is used by schools where a child is attending an approved educational activity. It is important to note that this will be under the supervision of a person considered by the school to have appropriate skills, training, experience and knowledge, to ensure the activity fulfills the educational purpose for which the pupil’s attendance has been approved by the school.

“The proposed code would not be an appropriate way for schools to record the attendance of children whose parents are responsible for their full-time education needs. It is not for the school to judge whether a child’s time outside of the school setting is appropriate to meet the parents’ duty under Section 7 of the Education Act in 1996 to ensure their child receives a suitable full-time education.

“Moreover, the school has no supervisory rule in the child’s education for the sessions they are not expected to be in school, and also has no responsibility for the welfare of the child while they are at home.”

It concludes: “Concerns have sometimes been raised that such absence may have a detrimental effect for the purpose of Ofsted inspection, but this is not the case. Many schools with significant flexi-schooling numbers have had good outcomes from Ofsted inspections.”