WHEN the Church agreed to ordain women priests in 1992, for some, it was an experience of freedom and justice; for others, it felt like the loss of a sacred order central to their faith.

Thirty years on, the Church debates same-sex relationships and prayers of blessing. Familiar themes of justice, doctrine, and group identity resurface. Stand-alone services of blessing will not be implemented for now because the cost is too high. But for whom? For many, the cost is pastoral failure from the Church’s chief pastors. For others, it is moral injury: the breakdown of meaning, trust, and ethical coherence.

Why do these questions strike so deeply at spiritual nerves? Many psychologists and some theologians recognise that our conflicts are rooted not only in doctrine and scripture, but more deeply in the psychology of belief: how faith expresses either love or fear. This shapes profoundly how Christians treat one another, and how the Church exercises pastoral care. This understanding highlights the contrast between mature and immature faith, while acknowledging that all are on a journey of becoming, shaped by grace and need.

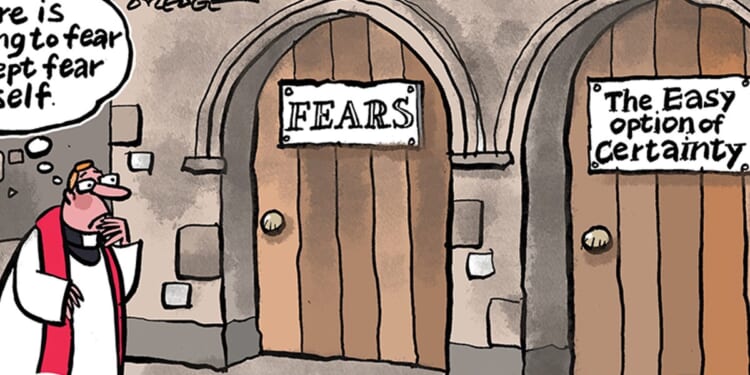

When debating structures, procedures, and legal processes, it is important to confront our fears — among them, fears about God, ourselves, our motives, and the cost of love. Only then can God begin to transform our anxieties rather than leave us to project them on to others.

AMONG religion’s less acknowledged functions is its capacity to defend against internal fears — anxiety, doubt, sexual desire, and echoes of trauma — where certainty feels safer than self-examination. These dynamics are not confined to any single theological position. Hostility to different sexualities can mask unacknowledged same-sex feelings, often described as reaction formation. Fear of women’s leadership can stem from insecurity about power and control.

Progressives’ tendency to label conservative views as prejudiced can serve two psychological functions: it removes the need for serious engagement with those arguments, thereby preserving the group’s moral certainty, and it reinforces group identity, also reducing complexity.

Such repression distorts theology and weakens pastoral care. If we cannot face our own shadows, we cannot hold another’s pain. Denial, in turn, breeds its own anxiety.

In times of cultural change, doctrines and the selective use of scripture can offer a sense of certainty, reinforcing conservative approaches to gender and sexuality. Here, certainty replaces trust; control replaces compassion. Listening stops; judgement begins. The LGBT+ community is marginalised, and those who struggle with sexuality, doubt, or mental health feel shamed rather than supported.

In Jesus’s teaching and example — so often missing from these debates — he challenges rule-based religion as interpreted and enforced by a privileged power group. He embodies radical inclusion, mercy, and justice. He dissolves boundaries of contagion and exclusion. Purity becomes compassion, not separation.

When the eucharist becomes a boundary marker of purity rather than a sacrament of reconciliation, something vital is lost. It echoes pre-Christian boundary-making. Christ did not create a gated community at his table; all shared the same bread and cup. As Jesus ate with those whose convictions differed from his, we, too, can share communion with those whose convictions differ from ours.

The Church does not become impure through contact with those with whom we disagree. We come to his table not as pure, but as forgiven. The bread and wine reconcile us, and in that shared meal the Church remembers who she is: the broken and yet beloved body of Christ. Purity draws lines; holiness breaks bread.

When the Church gives priority to legal formulas, processes, and procedures rather than pastoral sensitivity, people suffer — and are still suffering — just as claims to defend truth so often damage people. Political expediency is labelled a fudge; doctrinal and scriptural certainty is labelled prejudice; claims for justice, as love writ large, seem largely ignored. Tension grows.

MANY inside and outside the Church now describe it as prejudiced, patriarchal, even immoral. Some accuse us of preaching one gospel and living another. The psychologist Gordon Allport described prejudice as “an antipathy based upon a faulty and inflexible generalisation . . . which places its target at a disadvantage”, noting that it fulfils a deep emotional need for those who hold it.

Arising from immature faith, religion can be used to protect the self by those who sincerely believe that they are defending the faith, and yet who may unintentionally spread fear, control, and exclusion, unable to handle human complexity — echoing failures within other national institutions that lose moral authority through similar dynamics. Such immaturity must be challenged if precious Christian insight is to be preserved from discredit. Otherwise, the Church’s voice becomes harder to hear.

Allport distinguishes mature faith as dynamic, self-critical, and centred in love —nurtured by returning to its source, not fear; open to truth; compassionate; and humble before mystery. Mature faith acknowledges its incompleteness and remains open to growth, recognising the call to live in the faith of God’s love, not the certainty of our own position.

When the Church learns again to love without fear, its pastoral care — reflecting the heart of Jesus Christ — will be felt by the marginalised. Jesus calls us not to control one another, but to set one another free.

The Revd Dr John Prysor-Jones is a specialist psychotherapist, a former lecturer in Counselling Psychology, and an international counselling consultant. He has permission to officiate in the diocese of St Asaph.