IN 1955, Archbishop Geoffrey Fisher was able to prevent Princess Margaret from marrying a war hero who had been divorced by appealing to her sense of duty and her need to set a Christian example to the nation. The two greatest poets of the day were serious Anglicans, as were two of the most popular writers, Dorothy L. Sayers and C. S. Lewis. The Church’s grip on the moral and cultural life of the nation seemed as assured as it had ever been.

It would be unfair to blame any archbishop for the scale of the subsequent collapse. The Church had been an integral part of a hierarchical and militarised England — as recently as 1990, the Archbishop of Canterbury was a man who had won the MC in action as a tank commander — and, when that country was washed away like a magnificent sandcastle by the tides of history, most of the Church went with it.

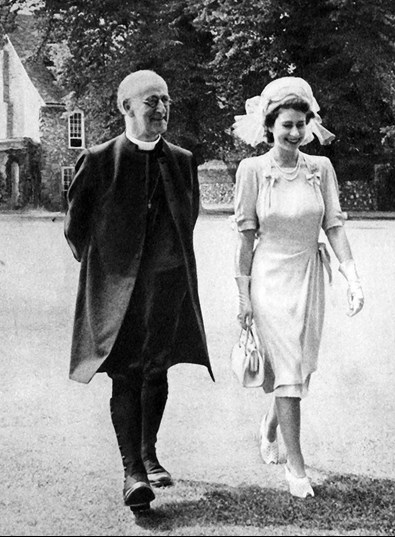

AlamyArchbishop Fisher with Princess Elizabeth in 1947 in the precincts of Canterbury Cathedral

AlamyArchbishop Fisher with Princess Elizabeth in 1947 in the precincts of Canterbury Cathedral

So, too, did the gradations of status and authority that had transmitted power down from the top. Bishops and, still more, archbishops had no way to get the Church or nation to do what they wanted — even when they wanted to make any change.

Few did. For Fisher, the first of this period, authority was not a problem. He had been a contented Marlburian and later the headmaster of another second-rank public school, Repton. His Church was still an integral part of the old governing class, drawn from a narrow social class. More than one third of the ordinands in his time had graduated from Oxford or Cambridge, as had been the case for the preceding 50 years.

His political powers were spent on the complex, time-consuming, and, in retrospect, largely pointless revision of canon law. The great tsunami of the 1960s which would sweep away the sandcastle Church was unforeseeable in his time.

His successor, Michael Ramsey, could see some of what was happening, and perhaps foresaw it, but he did so from a position of confident, rather saintly, scholarship. (His brother Frank, who died young, had been a genius: a ground-breaking mathematician, a friend and collaborator of Wittgenstein’s, and an atheist.) When told that the commission that he had set up to study the Church’s attitude to divorce was working very slowly and might need nine volumes for its conclusions, Archbishop Ramsey replied that nine volumes would be “very . . . serviceable”.

The collapse of churchgoing in the later part of the 1960s could not possibly be blamed on Ramsey: he spent much of his political capital on a scheme for unity with the Methodists which might have been a sensible response. It was, perhaps, the last time that the Church of England could enter such negotiations from a position of strength, but an alliance between conservative Anglo-Catholics and Evangelicals wrecked the idea. The Catholic party would, in turn, be wrecked by the ordination of women, but, though Ramsey could see no theological objections to that change, there was no serious talk of making it in his time.

Under Ramsey, too, the General Synod came into being. The withdrawal of power from Parliament was a recognition that the Church of England was no longer one of the underpinnings of national political life, even if it would take the Church and the new Synod several decades to realise this. Certainly, Ramsey’s successor, Donald Coggan, did not. His “Call to the Nation” was an appeal to the ghosts in the pews, scarcely audible to the living. There was something rather splendid in his open-hearted inability to understand the Vatican: he called both for the ordination of women and for the full intercommunion of the two Churches, but no one doubted his sincerity or goodness. Numerical decline continued unabated.

UNDER his successor, Robert Runcie, the cracks around the Church’s position in society opened into a crevasse. His instincts were those of a one-nation Conservative. As a tank commander who had fought across Europe from D-Day to Belsen, he had none of the illusions about war which swept the country during the Falklands conflict. This earned him the hostility of the Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, whose theological advisers were Evangelical and, therefore, opposed to him on principle as a liberal Catholic.

The traditionalist Catholics were implacably opposed, because of his sympathy for women priests; and the supporters of women’s ordination saw that he was dragging his feet to avoid a schism that they thought inevitable and, perhaps, desirable, too.

The Evangelical counter-attack focused on homosexuality, an issue on which Runcie’s position was vulnerable. His instincts and those of his sympathisers were with a policy of reticence (“Don’t ask, don’t tell”); but the Evangelical party in the Synod was determined to ask, and an increasing number of gay clergy were happy to tell. The closeted gays who had thrived under the old regime were, in many instances, corrupt, and a series of scandals damaged the Church and him personally.

Still, it came as a real shock when the Evangelicals around Thatcher arranged for George Carey to succeed him. Carey was an outsider from a secondary modern, who fiercely resented the condescension of the old Establishment. He had been an excellent and inspiring vicar and a competent bishop. He saw that the Church faced a crisis of irrelevance — he warned that it might become “a toothless old woman muttering to herself in a corner” — and he had a clear plan for what needed to be done. He wished to centralise the decision-making into one body that would control both the finances and the administration. But he lacked the political and rhetorical skills to carry this through.

His determination pushed through the ordination of women, and pushed out the irreconcilable Anglo-Catholics. He seemed to think that he could run the Church like a very large parish and he called himself the “Vicar to the Nation”. His Decade of Evangelism brought nothing but accelerated numerical decline.

AlamyArchbishop Coggan (left) with Cardinal Hume at a rally in Trafalgar Square in support of the Northern Ireland Peace Movement, November 1976

AlamyArchbishop Coggan (left) with Cardinal Hume at a rally in Trafalgar Square in support of the Northern Ireland Peace Movement, November 1976

It was an understandable temptation to look away from the dispiriting spectacle at home towards the growth elsewhere in the world. Carey boasted that the Anglican Communion had 80 million members worldwide. Fifty million of those supposed Anglicans were meant to be British, even if only one in 50 of them actually went to church.

Most other things about the Communion were as phoney as that statistic. It made no sense to observers from other denominations, because its decisions were not binding on anyone. The incoherence of the Communion had been conclusively demonstrated after the 1988 Lambeth Conference, when the American liberals ignored Runcie’s calls for restraint and consecrated a woman bishop. But it suited church politicians in England to pretend that the Communion mattered. It increased their self-importance and visibly diminished the power of any Archbishop of Canterbury, even over his own Church.

After its initial use by the liberals as a weapon for women’s ordination, the Communion became the most powerful weapon in the armoury of the sexual conservatives. It became an enormous drag on the time and strength of successive Archbishops, because the only way in which it could ever even seem to reach decisions was by personal diplomacy among the Primates.

WHEN Carey went, there was an outpouring of liberal hope and joy at the appointment of Rowan Williams, who seemed a return to the tradition of saintly scholarship. But he was incapable of management and uninterested in leadership. With the ordination of women a fairly settled question, political struggles in the Church now centred on homosexuality.

The conservative majority in the Communion took a keen interest in these, some even ordaining “missionary bishops” in England to counteract what they saw as liberal rot. Williams, whose own eloquent sympathies for gay clergy were well known before his appointment, allowed himself to be bullied into a position in which his acknowledged personal views were officially regarded as heretical by the Communion that he notionally led. The Church in England continued to shrink into irrelevance, as did all forms of Christianity in this country, except for those supported by immigrants who were not, for the most part, Anglicans: the Roman Catholics and the Charismatic Evangelicals.

Justin Welby was the candidate of Charismatic Evangelicalism in the Church of England. He succeeded Williams partly because he impressed the CNC as the only one at interview who took seriously the problems of numerical decline. He had very limited experience as a diocesan bishop, in Durham, but had set out a brisk programme to put the diocesan finances on a firm footing. It failed, like all other similar attempts. But he came into office in a nimbus of charm and energy, with a reputation as a manager who got things done.

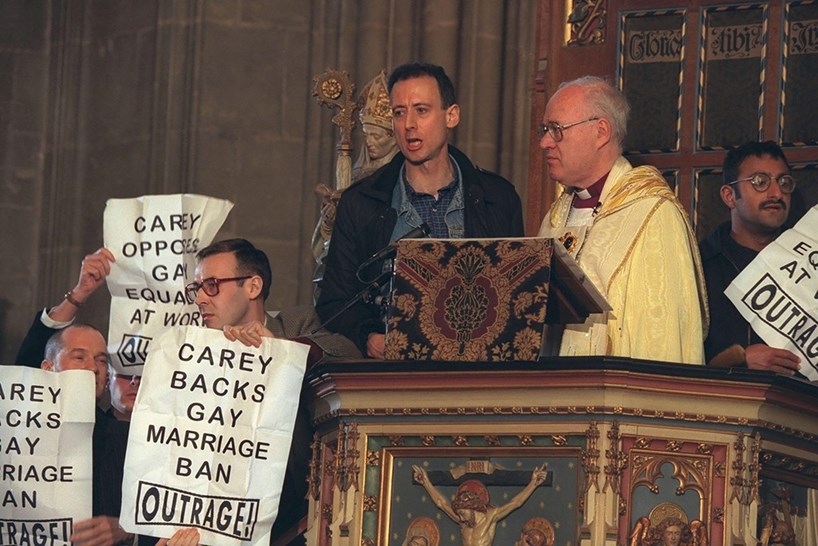

AlamyPeter Tatchell and others OutRage protesters interrupt Archbishop Carey’s sermon in his cathedral at Easter 1998

AlamyPeter Tatchell and others OutRage protesters interrupt Archbishop Carey’s sermon in his cathedral at Easter 1998

The problem, as it emerged, was that he was a leader who did not understand management. His political skills worked on a human scale, not on impersonal groups. He could inspire people who shared his aims and objectives, but he could not set up the organisational structures that would work with the indifferent or the hostile. His attempt to resolve the schism over homosexuality gave institutional form to the deadlock between liberals and conservatives: it offered neither side any incentive but love and faith to change their minds, and that is not how church politics works.

Liberals distrusted him as a tool of the HTB mafia, while the Evangelicals thought him a liberal sell-out. His defence of asylum-seekers offended the right-wing press.

When he was confronted with a backlog of horrendous abuse cases, his instinct was to throw management and experts at the problem. Very few of these were first-rate. Some were deadweight or worse. This alienated the managed — of the making of safeguarding courses there was no end — without satisfying the survivors’ lobby, whose demands soon escalated to a full-scale clear-out of bishops and church civil servants.

This alliance, egged on by grossly unfair media coverage, forced him out of office in undeserved disgrace, leaving as a problem for his successor an unmanageable and leaderless Church of England, stripped at last of pretension, to match its loss of power.