“WAS Tennyson ever young?” asks Richard Holmes, the celebrated biographer of Shelley and Coleridge. His absorbing account of “young” Tennyson takes us — in a sense familiar to Church of England people — to the poet’s late forties.

We follow precocious Alfred’s upbringing, one of 11 children, in a vicarage terrorised by his scholarly, drunken father.

Cambridge brings lifelong friends, and Holmes particularly keeps track of Tennyson’s great supporter Edward FitzGerald, of Omar Khayyam fame.

It is astonishing that, within three years of university, Tennyson had written some of his best-known poems: “The Lady of Shalott”, “Morte d’Arthur”, “Ulysses” — the last two in the shadow of the sudden death of his dear friend Arthur Hallam, to be commemorated in the great sequence In Memoriam.

The following years were restless, as the poet shunted between family and friends, London lodgings and the deserted beach at Mablethorpe, and unhappy love affairs.

Tennyson’s annus mirabilis was 1850, with the final publication, to great acclaim, of In Memoriam; his marriage two months later, after a long and fraught courtship, to Emily Selwood; and his appointment as Poet Laureate. He was 41.

He settled grandly on the Isle of Wight; “The Charge of the Light Brigade” took the public by storm; he grew a big beard, and started to become a literary monument.

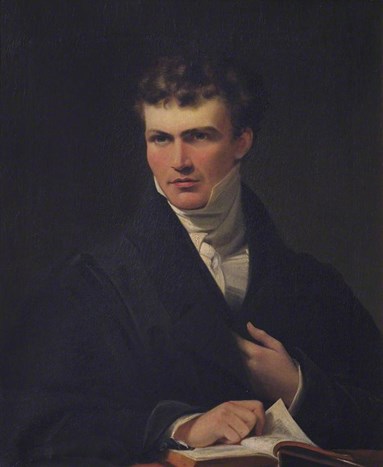

AlamyWilliam Whewell, Tennyson’s influential scientific tutor at Trinity College, Cambridge. From the book

AlamyWilliam Whewell, Tennyson’s influential scientific tutor at Trinity College, Cambridge. From the book

Much of this is familiar from other biographies. The originality of The Boundless Deep (a phrase from the much-loved “Crossing the Bar”) is its detailed demonstration that “During this turbulent early period, Tennyson’s thought and poetry were fired and animated by the new science and the new scepticism; by ideas of geology and deep time; the vastness, beauty and terror of the new cosmology.”

Holmes builds on his earlier study of the impact of science on the Romantic generation, The Age of Wonder, and establishes how engaged Tennyson was with scientific developments during these years before On the Origin of Species.

In Memoriam had its own evolution over two decades, as the scepticism opened up by science found a place in the poems alongside intense grief for Hallam: “There lives more faith in honest doubt, Believe me, than in half the creeds.” The prefatory poem “Strong Son of God, immortal Love” — later known as a hymn — was, in fact, the last to be added. Holmes sees it as a statement of faith, designed in part to reassure the devout woman to whom Tennyson was about to propose.

Church Times readers may be mildly shocked to find the Apocalypse referred to as “Revelations”; and puzzled to read that Tennyson’s friend F. D. Maurice was “dismissed by London University for his unorthodox and liberal views on education” rather than dismissed by King’s College for his views on everlasting punishment.

With imagination, authority, and humour, Holmes has given us a new perspective on Victorian poetry’s biggest beast, and sends us back to the poems with fresh eyes.

The Revd Philip Welsh is a retired priest in the diocese of London.

The Boundless Deep: Young Tennyson, science and the crisis of belief

Richard Holmes

HarperCollins £25

(978-0-00-738693-2)

Church Times Bookshop £22.50